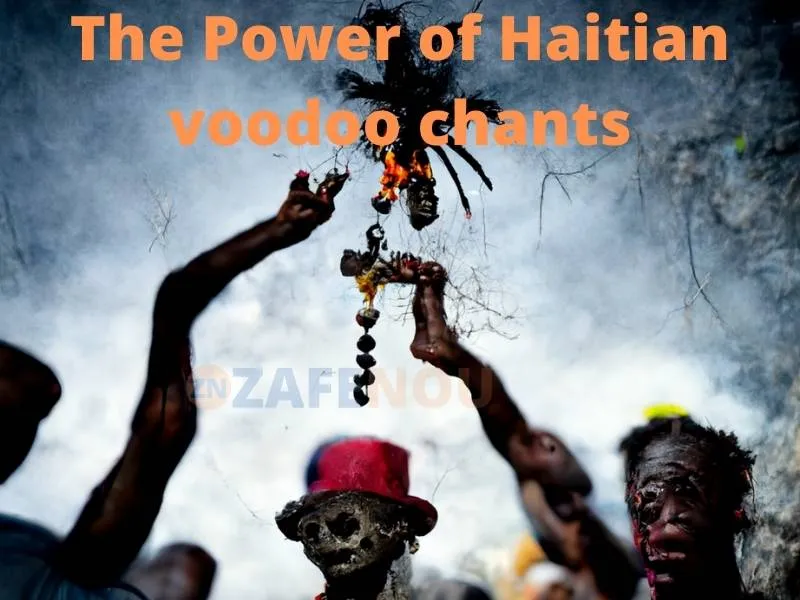

Haitian Vodou chants are far more than simple songs; they are the spiritual heartbeat of a complex religious tradition that has survived centuries of suppression and misunderstanding. For practitioners in Haiti and the diaspora, these vocal traditions serve as the primary method of communication between the physical world and the spiritual realm.

Unlike the Hollywood depictions of dark magic and eerie spells, genuine Vodou chants are expressions of devotion, history, and community solidarity.

These musical traditions are deeply intertwined with the history of the Haitian people, preserving African linguistic roots and blending them with Caribbean influences. The chants function as prayers, historical records, and tools for inducing the trance states necessary for religious ceremonies.

Understanding these chants requires looking beyond superficial myths to see a sophisticated system of worship that honors ancestors and nature spirits known as the Lwa.

In a typical ceremony, the interplay between the lead singer, the chorus of initiates, and the drummers creates a powerful sonic environment. This atmosphere is designed to invite spiritual presence and facilitate healing for the community.

This article explores the structure, purpose, and cultural significance of these sacred songs, shedding light on how they function within the broader context of Haitian spirituality.

The Spiritual Foundation of Vodou Music

Music in Haitian Vodou is not background entertainment; it is a liturgical technology used to open the gates between worlds. The central belief is that sound, specifically the combination of voice and drum, generates the energy needed to summon the Lwa. This energy is often referred to as “heating up” the temple, or peristyle. Without the correct songs sung in the correct order, the spirits cannot manifest, and the ceremony cannot proceed.

The vocal component is led by a spiritual leader, either a priest (Houngan) or priestess (Mambo). They act as the cantor, initiating songs that correspond to the specific spirit being honored at that moment. The congregation, often including a dedicated choir of initiates known as hounsis, responds in a call-and-response pattern. This structure mirrors West African musical traditions and ensures that every participant is actively engaged in the ritual work.

Accompanying the chants is the asson, a sacred rattle made from a dried gourd and covered in a mesh of beads or snake vertebrae. The Houngan or Mambo uses the asson to keep time and signal changes in the liturgy. The sound of the rattle cuts through the drumming and singing, serving as a conductor’s baton that directs the flow of spiritual energy. It is a symbol of authority and a practical tool for maintaining the rhythm of the service.

The Distinction Between Rada and Petwo Rites

Haitian Vodou is divided into different rites, or nanchon (nations), each with its own distinct musical style, rhythms, and temperament. The two most prominent rites are Rada and Petwo. Understanding the difference between them is essential for grasping the complexity of Vodou chants, as the music for each is radically different in tone and purpose.

The Rada Rite

Rada chants are generally cool, balanced, and reverent. They trace their origins to the Dahomey kingdom (modern-day Benin) and honor spirits that are considered benevolent, wise, and gentle. The music in Rada ceremonies is characterized by complex but steady polyrhythms played on the Tanbou Rada drums.

The singing style is melodic and often sounds like a solemn prayer. These chants are used to ask for peace, wisdom, and stability.

The Petwo Rite

In contrast, Petwo chants are hot, aggressive, and rapid. This rite evolved in Haiti during the brutal conditions of slavery and is associated with the revolutionary spirit of 1804. The music utilizes the sharp crack of a whip and the frenetic beat of the smaller, higher-pitched Petwo drums.

The singing is forceful, often utilizing shorter, more repetitive phrases designed to build intensity quickly. Petwo spirits are called upon for protection, swift justice, and handling difficult, immediate problems.

The Role of Drummers and the Ogan

While the human voice carries the lyrical message, the drums provide the language that the spirits understand. In Haitian belief, the drums themselves are sacred objects that undergo baptism rituals. A master drummer, known as the Tanbourinè, must know hundreds of specific rhythms, as each spirit responds to a unique beat. If the drummer plays the wrong rhythm while the choir sings a specific chant, the spirit will not appear, or the energy of the ceremony will collapse.

The rhythmic foundation is held together by the Ogan, a flattened iron bell or hoe blade struck with a metal rod. The Ogan plays a piercing, unvarying timeline pattern that serves as the reference point for all other musicians and singers.

Even as the drumming becomes incredibly complex and the singing reaches a fever pitch, the steady clang of the Ogan keeps the collective grounded.

The interaction between the drummers and the singers is dynamic. If the energy in the room feels low, the Houngan may switch to a faster, more popular chant to energize the crowd. The drummers will immediately respond by intensifying their attack. Conversely, if the energy becomes too chaotic, the leader may switch to a slower, calming song to bring the room back to a state of equilibrium.

Language and Ancestral Memory

The lyrics of Vodou chants are a linguistic mosaic that preserves the history of the Haitian people. Most songs are sung in Haitian Kreyòl, making them accessible to the community. These lyrics often tell stories about the attributes of the spirits, recount historical events, or offer proverbs about moral behavior. For example, a song for the spirit Papa Legba might ask him to “open the gate” so that the other spirits may enter.

However, many chants also contain fragments of Langaj. This term refers to sacred words and phrases derived from various West and Central African languages, such as Fon, Yoruba, and Kikongo. Over centuries, the literal meanings of some Langaj phrases may have been lost to the general population, but their ritual power remains. When practitioners sing in Langaj, they are affirming their direct lineage to Africa and maintaining a sonic link to their ancestors.

This preservation is significant because it resisted the colonial effort to erase African culture. By encoding their history, genealogy, and religious philosophy into song, enslaved Africans and their descendants ensured that their worldview could survive even when written records were forbidden. Every ceremony is, in effect, a history lesson sung in the presence of the community.

Spirit Possession and the Chwal

The ultimate goal of many Vodou ceremonies is possession, where a Lwa temporarily displaces the consciousness of a participant to interact with the community. The person being possessed is referred to as the chwal (horse) of the spirit. Chants are the primary trigger for this phenomenon. When a specific spirit’s song is sung with sufficient intensity, it invites that entity to ride their “horse.”

Observers often describe a visible shift in the atmosphere when the right chant locks in with the drumming. The chwal may begin to move differently, adopting the mannerisms associated with the spirit. For instance, if the spirit Ogou (a warrior entity) arrives, the music becomes martial and bold. If Ezili Freda (a spirit of love and luxury) arrives, the chanting becomes flirtatious and sweet.

Once the spirit has arrived, the singing often shifts to direct conversation. The congregation may sing songs of welcome, or the spirit may lead a song to deliver a message to the people. In this context, the chant is not just a performance but a dialogue. The community sings to the spirit, and the spirit, through the possessed individual, sings back.

Misconceptions Regarding Spells and Curses

Popular culture frequently misrepresents Haitian Vodou chants as incantations for casting hexes or animating dolls. This sensationalized view ignores the religion’s focus on healing and balance. In reality, the vast majority of chants are devotional.

They are prayers for health, protection, gratitude, and guidance. The “magic” in Vodou is generally understood as the manipulation of natural energies to restore harmony, not to inflict arbitrary harm.

There are, of course, secret societies and more aggressive aspects of the tradition, as exists in many religions. However, the public ceremonies where chanting is most prominent are communal affairs. The songs are designed to strengthen the bond between the members of the sosyete (society) and their patrons in the spirit world. The fear associated with these chants often stems from historical prejudice rather than the actual content of the lyrics.

Practitioners view the chants as tools for spiritual hygiene. Just as one might clean a house, specific songs are used to cleanse the spiritual atmosphere of a temple or a person. This is often done during a Lave Tèt (head washing) ceremony, where songs of purification help to clear the mind and settle the spirit. The intent is almost always constructive, aiming to fortify the individual against the hardships of life.

FAQ

What is the difference between a hymn and a Vodou chant?

While both are religious songs, Vodou chants are functionally different from standard Christian hymns. A hymn is typically a song of praise or worship sung by the congregation. A Vodou chant, while also devotional, is often a functional tool used to trigger a specific spiritual event, such as the arrival of a spirit or the consecration of an offering. The rhythm and vibration of the chant are considered just as important as the lyrics in achieving the ritual’s goal.

Can anyone learn Haitian Vodou chants?

The chants are traditionally learned orally by attending ceremonies and listening to the elders. There is no formal sheet music in the traditional context. While anyone can listen to recordings, true mastery of the repertoire requires initiation and years of participation in a sosyete. The songs are complex, often requiring knowledge of Langaj and the specific rhythmic breaks associated with different spirits.

Do the chants change depending on the location?

Yes, there is significant regional variation in Haiti. A song sung for the spirit Agwe in the north of Haiti might have a different melody or slightly different lyrics than one sung in the south. However, the core rhythms and the fundamental attributes of the spirits remain consistent. These regional differences add to the richness of the tradition, reflecting the local history of different communities.

Are instruments always used with the chants?

Most public ceremonies involve the full battery of drums, bells, and rattles. However, there are specific types of rituals, often related to mourning or deep esoteric work, that may be performed a cappella or with minimal percussion. In the Gede rite, which honors the spirits of the dead, the music can be raucous and less formal, sometimes using improvised instruments.

What is the role of the chorus in these songs?

The chorus, or hounsis, acts as the battery that powers the ceremony. The Houngan or Mambo provides the spark by starting the song, but the chorus sustains the energy. Their job is to sing with volume and conviction. In Vodou belief, a weak chorus results in a weak ceremony, as the spirits are attracted to the vitality and heat generated by the group’s collective voice.

Is it disrespectful to listen to these chants if you are not an initiate?

Listening to recordings of Vodou music is generally considered acceptable and is a way for outsiders to appreciate the cultural artistry of Haiti. Many folkloric groups perform these songs publicly. However, mimicking rituals or using sacred songs out of context without understanding their meaning can be seen as trivializing a deep religious tradition. Respect and context are key.