In the dimly lit sanctuary of a Haitian Vodou temple, or peristil, a priest bends toward the earth with intense concentration. Between his thumb and forefinger, he holds a pinch of cornmeal, releasing it in a steady, fluid stream to create intricate geometric patterns on the ground.

These drawings are known as vèvè (or veve). They are not merely decorative art or random sketches; they are complex spiritual technologies used to communicate with the invisible world. For practitioners of Vodou, the vèvè serves as a beacon, a landing strip, and a sacred invitation for the Lwa (spirits) to enter the human realm.

To the uninitiated observer, these diagrams may look like beautiful symmetry, but to the faithful, they are a language of power and history. This guide explores the deep significance of vèvè, the skilled techniques used to create them, and the specific meanings behind the symbols associated with the major spirits of the Vodou pantheon.

The Spiritual Function of the Vèvè

A vèvè acts as a central focal point for ritual energy. In Haitian Vodou cosmology, the universe is divided into the visible world of the living and the invisible world of the spirits, known as Ginen.

The vèvè is drawn at the poto mitan, the center post of the temple, which serves as the vertical axis connecting these two domains.

When a Houngan (priest) or Mambo (priestess) traces a vèvè, they are essentially writing a letter of invitation to a specific spirit. The diagram concentrates the psychic energy of the participants and defines the sacred space where the spirit will manifest.

It is believed that the Lwa recognizes their own signature and is compelled to descend when the ceremony is performed correctly.

The symbol also serves a protective function. By grounding the energy of the spirit in a specific geometric form, the priest ensures that the interaction remains controlled and beneficial for the community. The drawing anchors the immense power of the Lwa, allowing the congregation to interact with the divine safely.

The Art of Tracing: Materials and Technique

Creating a vèvè requires years of practice and a steady hand. There are no stencils or rulers used; the artist must rely entirely on muscle memory and spiritual focus. The priest takes a handful of powder and releases it through the fingers, regulating the flow to create lines that are remarkably thin and uniform.

The primary material used is plain cornmeal (farine maïs). Cornmeal represents food, life, and the earth, making it an ideal offering to the spirits. However, the substance may change depending on the nature of the spirit being invoked or the specific rite being performed.

- Cornmeal or White Flour: These are the standard materials for the Rada spirits, who are generally considered cool, benevolent, and ancient.

- Wood Ash: Often used for the Guédé family of spirits, who govern death, ancestors, and the cemetery. The grey ash symbolizes the transition between life and decay.

- Coffee Grounds: Sometimes mixed with ash or used alone for specific earth-bound spirits to provide a strong, aromatic anchor.

- Gunpowder: In ceremonies for Petro spirits—who are fiery, hot, and aggressive—gunpowder may be incorporated into the design. This allows the vèvè to be ignited, creating a flash of heat that mirrors the spirit’s intensity.

Interpreting the Geometry: Common Motifs

While every Lwa has a unique signature, vèvè share a common visual language rooted in West African traditions, specifically those of the Fon and Kongo peoples. The designs are almost always symmetrical, radiating outward from a central axis. This symmetry represents balance and the mirroring of the physical and spiritual realities.

The Cross is one of the most frequent elements. While it bears a resemblance to Christian iconography due to historical syncretism, in Vodou, it primarily represents the crossroads. It signifies the four cardinal points and the intersection where the human world meets the divine.

Geometric Flourishes such as stars, circles, and triangles are used to direct energy. A closed circle often represents containment and the womb, while arrows or jagged lines indicate movement, defense, and speed. These abstract shapes are often combined with literal pictograms—swords, hearts, boats, or snakes—that identify the specific attributes of the spirit.

Major Lwa and Their Distinctive Vèvè

There are hundreds of Lwa in the Vodou tradition, and variations of vèvè exist between different temple houses (sosyete). However, the core symbols for the major spirits remain largely consistent and recognizable.

Papa Legba: The Guardian of the Crossroads

Legba is the first spirit saluted in any ceremony because he holds the keys to the spiritual gate. Without his permission, no communication with other spirits is possible. His vèvè typically features a central cross intersecting a vertical line.

You will often see a cane or a crutch depicted, representing his appearance as an old man, alongside keys or a machete. The design emphasizes intersection, symbolizing his role as the ultimate translator between worlds.

Damballah Wedo: The Cosmic Serpent

Damballah is the benevolent Sky Father and the primordial creator. His vèvè is dominated by the image of two snakes, often arching symmetrically around a central pole or an egg. The snakes represent Damballah and his companion, Ayida Wedo (the rainbow).

The design is fluid and curved, lacking the sharp angles of more aggressive spirits, reflecting his cool, peaceful, and wise nature. It represents the source of life and the connection between the waters of the earth and the waters of the sky.

Erzulie Freda: The Spirit of Love and Luxury

Erzulie Freda is the Lwa of romantic love, beauty, and perfection. Her symbol is the heart, but it is rarely a simple shape. It is usually elaborated with intricate, lace-like scrollwork that speaks to her love of finery and jewelry.

Often, a sword or dagger pierces the heart. This is not a symbol of violence, but rather an acknowledgment that deep love often carries the potential for deep pain or sorrow. Her vèvè demands precision and beauty, mirroring her high standards.

Ogou Feray: The Warrior of Iron

Ogou is the spirit of iron, war, technology, and political power. His vèvè is sharp, angular, and distinct. It almost always features a sword, a machete, or an iron spike stuck into the earth.

The design conveys strength, stability, and defense. Unlike the fluid curves of Damballah, Ogou’s lines are direct and piercing, representing the ability to cut through obstacles and the transformative power of fire and metal.

Baron Samedi: Lord of the Cemetery

As the head of the Guédé family, Baron Samedi governs the transition from life to death. His vèvè is a stark reminder of mortality. It features a cross standing upon a pedestal that represents a tomb or coffin.

The design is often flanked by grave digger’s tools, sunglasses (which he wears to protect his eyes from the living), or skeletal imagery. Despite the somber imagery, the Baron is also a healer and a protector of children, and his vèvè is a request for protection against premature death.

Agwé: Ruler of the Seas

Agwé (or Agoué) rules over the ocean and protects all who travel by water. His vèvè is a literal depiction of his domain. It centers on a boat, often referred to as the “Imamou,” complete with masts, sails, and oars.

The drawing may be embellished with fish, shells, or waves. Ceremonies for Agwé are often elaborate, sometimes involving the construction of a raft laden with offerings that is pushed out to sea.

The Ritual Lifecycle of a Vèvè

One of the most profound aspects of the vèvè is its impermanence. Unlike religious icons in many other traditions, such as statues or stained glass, a vèvè is not meant to last. It is created specifically for the “now” of the ceremony.

Once the vèvè is drawn and consecrated with libations (offerings of water or alcohol), the ceremony reaches its peak. The participants dance around the center post, and eventually, they dance directly upon the vèvè. The movement of feet destroys the drawing, blending the cornmeal with the earth.

This destruction is not an act of disrespect; it is the completion of the ritual. It signifies that the spirit has arrived and “consumed” the offering. The energy contained in the diagram is released and absorbed by the faithful. By the end of the night, the beautiful geometric art has vanished, having served its purpose of bridging the gap between the human and the divine.

Historical Origins and Cultural Significance

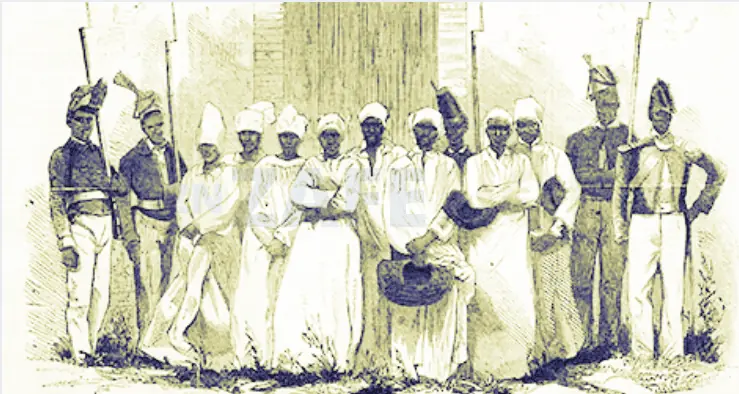

The practice of drawing vèvè traces its roots back to the Dahomey kingdom (modern-day Benin) and the Kongo region of Central Africa. When enslaved Africans were brought to Haiti (then Saint-Domingue), they carried these visual traditions with them.

In the New World, these disparate African practices blended with influences from Indigenous Taino culture and French Catholicism to form Haitian Vodou.

Historically, the vèvè may have also served a practical purpose during the era of slavery. Because the symbols could be drawn on the ground with readily available materials like flour or ash and then quickly wiped away, they allowed enslaved people to practice their religion in secret.

If overseers approached, the evidence of the ritual could be erased in seconds.

Today, the vèvè stands as a testament to resilience. It is a visual language that has survived centuries of suppression, preserving the theology and identity of the Haitian people. It remains a vital, living art form that continues to evolve within the community.

FAQ

Can anyone draw a vèvè?

Technically, anyone can attempt to draw the shapes, but in a ritual context, a vèvè is only considered “active” or authentic if drawn by an initiated priest (Houngan) or priestess (Mambo). The authority to summon the Lwa comes from the initiation process (kanzo), not just the artistic ability to replicate the design.

Are vèvè symbols permanent?

No, vèvè are inherently temporary. They are drawn on the floor of the temple specifically for a ceremony and are destroyed during the course of the ritual. The act of dancing over the vèvè and obliterating the lines is a crucial part of the energy transfer between the spirits and the community.

Why is cornmeal the most common material?

Cornmeal is an organic substance that represents sustenance and the harvest. In Vodou, it is considered a pure material that feeds the spirits. Because it is biodegradable and comes from the earth, it is the ideal medium for a drawing that is meant to be absorbed back into the ground.

Do the symbols change over time?

While the core elements of a vèvè (like Legba’s cross or Erzulie’s heart) remain consistent, there is room for artistic variation. Different lineages or temple houses may have their own stylistic flourishes. A vèvè is often a personal signature of the priest’s relationship with that spirit, so minor details may vary from one temple to another.

Is a vèvè the same as a magic circle?

While they share similarities in that both define a sacred space, a vèvè is more specific. It is not just a boundary; it is a calling card or a beacon for a specific entity. Unlike a generic circle of protection, a vèvè contains specific information about the identity, attributes, and preferences of the spirit being invoked.

Can vèvè be used as tattoos or art?

In recent years, vèvè have appeared in secular art and tattoos. While this is often done out of appreciation for the aesthetic, traditional practitioners view these symbols as sacred and functional. Placing a “calling card” for a spirit permanently on one’s body is considered a serious spiritual commitment that should be understood fully before being undertaken.