The history of Haitian Vodou is inextricably linked to the political and social evolution of Haiti itself. While the religion served as a unifying force during the Haitian Revolution of 1791, the post-independence era brought new challenges as leaders sought legitimacy on the global stage. One of the most significant and damaging events in this timeline is the Bizoton Affair of 1864.

This controversial trial, held in Port-au-Prince, involved accusations of ritual murder and cannibalism against a group of Vodou practitioners. The event was not merely a legal proceeding; it was a calculated political spectacle orchestrated by the administration of President Fabre Geffrard. The trial aimed to suppress traditional spiritual practices and demonstrate Haiti’s alignment with Western, Christian values.

The repercussions of the Bizoton Affair extended far beyond the courtroom. It provided ammunition for foreign critics to label Haiti as “uncivilized,” fueling racial stereotypes that persisted for over a century. Understanding this trial requires examining the complex interplay between the Haitian state, the Catholic Church, and the resilient spiritual identity of the Haitian people.

The Political Context: Geffrard and the Vatican Concordat

To understand why the trial occurred, one must look at the political climate under President Fabre Geffrard. Geffrard, who came to power in 1859, was determined to modernize Haiti and gain diplomatic recognition from European powers and the United States. A central pillar of his strategy was strengthening ties with the Roman Catholic Church.

In 1860, Geffrard signed a historic Concordat with the Vatican. This agreement formally re-established the Catholic hierarchy in Haiti, which had been largely absent since the revolution. The Concordat brought an influx of French clergy who were eager to evangelize the population and stamp out what they viewed as pagan superstition.

The presence of these new clerical authorities created immediate tension with the practitioners of Vodou, the faith of the majority. For Geffrard, suppressing Vodou became a way to prove to the Vatican and foreign diplomats that Haiti was a “civilized” nation worthy of respect.

The state needed a public example to demonstrate its commitment to eradicating traditional practices, setting the stage for the persecution that followed.

The Bizoton Affair: Allegations and Arrests

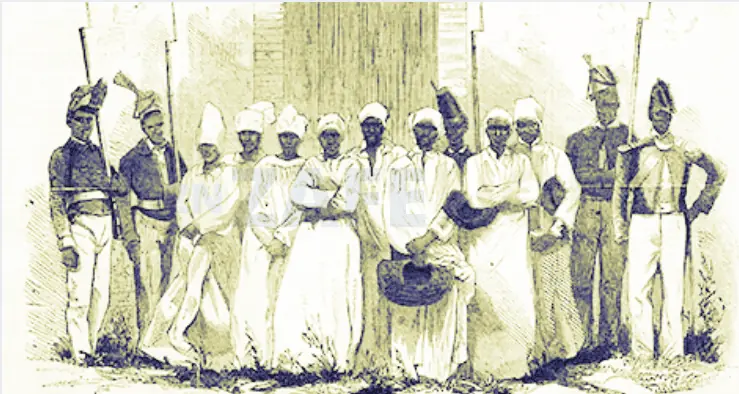

In late 1863, authorities arrested a group of individuals in the Bizoton district, just outside Port-au-Prince. The central figures were Congo Pellé and his sister, Jeanne Pellé. They were accused of abducting a 12-year-old girl named Claircine, who was reportedly Jeanne’s niece, for the purpose of a ritual sacrifice.

The charges were sensational and gruesome. The prosecution alleged that the child had been strangled, flayed, and consumed in a ritual intended to gain spiritual favor. These accusations mirrored the “blood libel” tropes often used in Europe to persecute minority groups. In the Haitian context, the charges were designed to shock the urban elite and foreign observers.

The legal proceedings were swift and heavily influenced by the executive branch. The accused were interrogated under duress, and historians have long questioned the validity of the confessions obtained. The trial was not an impartial search for truth but a performative rejection of African-derived spirituality. In February 1864, eight people were executed by firing squad in a public display intended to terrify practitioners of the faith.

Spenser St. John and the Construction of a Narrative

A key figure in the legacy of the Bizoton Affair was not a Haitian official, but a British diplomat named Spenser St. John. Serving as the British Chargé d’Affaires in Haiti during the trial, St.

John took a keen interest in the proceedings. He used the trial as the centerpiece for his later book, Hayti, or the Black Republic.

St. John’s account of the trial was lurid and exaggerated. He extrapolated from this single, dubious legal case to claim that cannibalism was a common feature of Haitian Vodou. His writings became the primary source of information about Haiti for the English-speaking world during the Victorian era.

The damage caused by St. John’s narrative was immense. His depiction of Haiti as a land of “Voodoo doctors” and savage rituals provided a moral justification for foreign intervention.

When the United States occupied Haiti in 1915, American officials and media frequently cited St. John’s claims to argue that the Haitian people were incapable of self-governance and needed to be “civilized” by external force.

Vodou Theology vs. The Prosecution’s Claims

The allegations made during the Bizoton trial fundamentally misrepresented the theology of Haitian Vodou. Vodou is a monotheistic religion that acknowledges a supreme creator, Bondye, and venerates spirits known as Lwa. The primary function of the religion is healing, community cohesion, and maintaining balance between the visible and invisible worlds.

Ritual sacrifice in Vodou is strictly limited to animals, such as chickens or goats, which are then cooked and shared among the community as a sacred meal. The concept of human sacrifice is anathema to the vast majority of Vodou lineages.

In Vodou cosmology, the taking of a human life creates a spiritual imbalance that brings harm to the perpetrator and their community.

The trial conflated the complex, structured religion of Vodou with sorcery or majik nwa (black magic). By blurring these lines, the prosecution successfully demonized the entire faith. The Houngans (priests) and Mambos (priestesses) who served as community leaders were portrayed as criminals, forcing many to practice their faith in secrecy to avoid arrest.

The Era of Anti-Superstition Campaigns

The execution of the Pellé siblings and their associates did not end the persecution of Vodou; it merely signaled the beginning of a more organized suppression. Following the trial and the solidification of the Catholic Church’s power, Haiti experienced periodic “Anti-Superstition Campaigns,” known locally as Rejeté.

These campaigns involved the state-sanctioned destruction of Vodou temples (ounfò), sacred drums, and ritual objects. Catholic clergy, often supported by the Haitian military, would travel to rural areas to force practitioners to renounce their Lwa and pledge exclusive allegiance to the Church. The Bizoton Affair served as the legal and moral precedent for these actions.

Despite these aggressive efforts, Vodou survived through syncretism. Practitioners continued to mask their devotion to the Lwa behind Catholic iconography. For example, the spirit Papa Legba was venerated using images of Saint Peter, while Ezili Freda was identified with the Mater Dolorosa. This adaptability allowed the religion to endure despite the state’s attempts to eradicate it.

Modern Historical Analysis of the Trial

Contemporary historians and anthropologists view the Bizoton Affair as a “show trial” driven by the geopolitical anxieties of the 19th century. Scholars note that the evidence presented was largely circumstantial and that the confessions were likely the result of torture or psychological pressure.

The trial is now understood as a clash between the Eurocentric aspirations of the Haitian elite and the Afro-centric reality of the Haitian peasantry. President Geffrard and his circle viewed Vodou as an obstacle to progress, a remnant of the past that needed to be purged for Haiti to join the community of modern nations.

In recent decades, there has been a significant shift in how the Haitian state relates to Vodou. The 1987 Constitution explicitly granted Vodou the status of a recognized religion, offering it the same legal protections as Catholicism and Protestantism. This marked a formal rejection of the legacy of the Bizoton Affair and an acknowledgment of Vodou’s central role in Haitian culture.

FAQ

What was the main charge in the Bizoton Affair?

The primary charge against the accused in the Bizoton Affair was the ritual murder and consumption of a 12-year-old girl named Claircine. The prosecution alleged that this act was performed to satisfy a spiritual pact. However, modern historians widely regard these charges as fabricated or heavily manipulated to serve the political agenda of the Geffrard administration.

Why did President Geffrard support the prosecution?

President Fabre Geffrard supported the prosecution to demonstrate Haiti’s “civilization” to Western powers. Having recently signed a Concordat with the Vatican, Geffrard wanted to show that his government was committed to Christian values and the suppression of “pagan” practices. The trial was a tool to solidify his alliance with the Catholic Church and gain diplomatic standing.

Who was Spenser St. John?

Spenser St. John was the British Chargé d’Affaires in Haiti during the 1860s. He is best known for his book Hayti, or the Black Republic, which detailed the Bizoton trial. His sensationalized and racially charged account of the event played a major role in spreading the myth that cannibalism was a standard practice in Haitian Vodou, influencing Western perceptions for decades.

Is human sacrifice a part of Haitian Vodou?

No, human sacrifice is not a recognized or accepted practice in Haitian Vodou. The religion focuses on healing, protection, and honoring ancestors. Offerings to the spirits (Lwa) typically consist of food, drink, and animal sacrifice (such as chickens), which are consumed by the community. The accusations in the Bizoton trial conflated the religion with criminal sorcery.

What was the Concordat of 1860?

The Concordat of 1860 was a treaty between the Haitian government and the Vatican. It formally re-established the Catholic Church’s hierarchy in Haiti, which had been disrupted since the revolution. The agreement allowed French priests to enter the country and gave the Church significant influence over education and social life, leading to increased friction with Vodou practitioners.

How did Vodou survive persecution after the trial?

Vodou survived through a process of syncretism and secrecy. Practitioners outwardly adopted Catholic rituals and identified their spirits with Catholic saints to avoid persecution. Ceremonies were often held in secret or disguised as social gatherings. This resilience allowed the faith to persist through the Anti-Superstition Campaigns until it eventually gained legal recognition.

Did the accused confess to the crimes?

The accused individuals did provide confessions, but historical records suggest these were obtained under extreme duress and intimidation. The legal standards of the time were not upheld, and the pressure to produce a guilty verdict for political reasons was immense. Consequently, the confessions are generally viewed by scholars as unreliable evidence of actual events.