What is Haitian Vodou? Haitian Vodou is a monotheistic religion from Haiti that blends West and Central African spiritual traditions with Roman Catholicism. Practitioners believe in one supreme creator, Bondye, and serve intermediary spirits called lwa (or loa) through ritual, song, and community ceremonies.

Developed between the 16th and 19th centuries in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, it is a life-affirming faith centered on healing, protection, and ancestral connection. Unlike Hollywood “voodoo” stereotypes of curses and dolls, Haitian Vodou is a complex theological system and was recognized as an official religion of Haiti in 2003. It remains a foundational pillar of haitian culture and identity worldwide. [Source: Britannica]

What is the Haitian Vodou religion

To understand what is the Haitian Vodou religion, one must look past the pop-culture “voodoo” mask and examine its monotheistic framework. Vodou practitioners do not worship multiple gods; rather, they serve a single God, Bondye, who is considered the ultimate source of life.

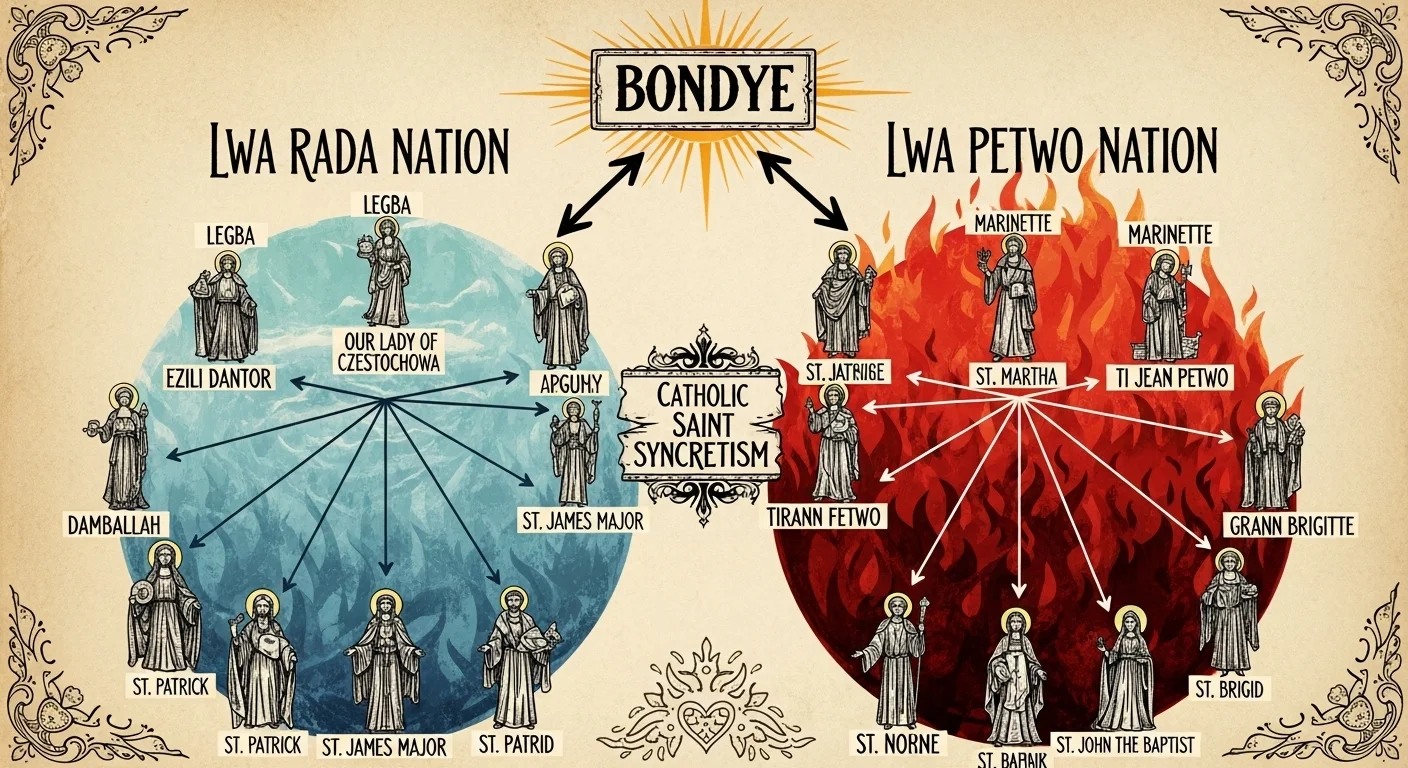

Because Bondye is transcendent and distant, the vodou pantheon consists of lwa—spirits who act as intermediaries. These spirits are divided into “nations” (nanchon), such as the cool, benevolent Rada and the hot, defensive Petwo. In every vodou ritual, specific lwa are called upon:

- Papa Legba: The guardian of the crossroads. No vodou ritual can begin without saluting him, as he opens the gate between the physical and spiritual worlds.

- Ogou: The spirit of iron and fire, representing the warrior spirit of the haitian people.

The nature of vodou is defined by syncretism. Historically, to survive the enslavement of the colony of saint-domingue, practitioners identified their spirits with catholic saints. For example, Ogou is often syncretized with Saint James the Greater, and the Lady of Mount Carmel is associated with Ezili Dantor. This vodou and catholicism overlap created a unique haitian religion that vodou developed into over centuries of resistance.

What is Vodou in Haiti

When asking what is vodou in haiti, you are looking at the country’s spiritual and social backbone. It is more than a religion; it is a way of life that dictates haitian society, music, and haitian art.

The center of vodou practice is the vodou temple, known as an ounfo. These are led by a vodou priest (oungan) or priestess (manbo). These leaders are pillars of the community, serving as healers and keepers of haitian folklore. Inside an ounfo, practitioners perform vodou ceremonies involving drumming, dancing, and the drawing of veve—sacred symbols on the floor that have been documented by the fowler museum of cultural history.

For much of haitian history, the haitian state suppressed the faith. However, a turning point occurred when it became an official religion in 2003 under the haitian government. This recognition meant allowing vodou priests the same legal rights as protestant or Catholic clergy. Today, traditional vodou is recognized as an official religion, moving from the shadows into the heart of the republic of haiti.

Haitian Vodou Myths & Misconceptions

The word voodoo is often used by outsiders as a tool of sensationalism. According to any reputable anthropologist, most “Hollywood voodoo” tropes are inaccurate.

- Myth: Voodoo dolls are used for curses. In the practice of vodou, dolls are actually used as tools for healing or as representations of lwa on an altar. They are rarely, if ever, used for harm.

- Myth: Vodou is evil. The claim that vodou is evil stems from colonial fears of the haitian revolution. It is a monotheistic faith focused on harmony and ancestral balance.

- Myth: Animal sacrifice is barbaric. In a vodou ritual, animal sacrifice is a sacred offering of life-force to the spirits. The meat is typically shared as a communal feast, serving both a spiritual and social purpose.

- Myth: Zombies are literal undead monsters. The “zombie” in haitian folklore is a profound metaphor for the trauma of slavery—a body without a soul. It is not a literal practice of the vodou religion.

Haitian Vodou History & Origins

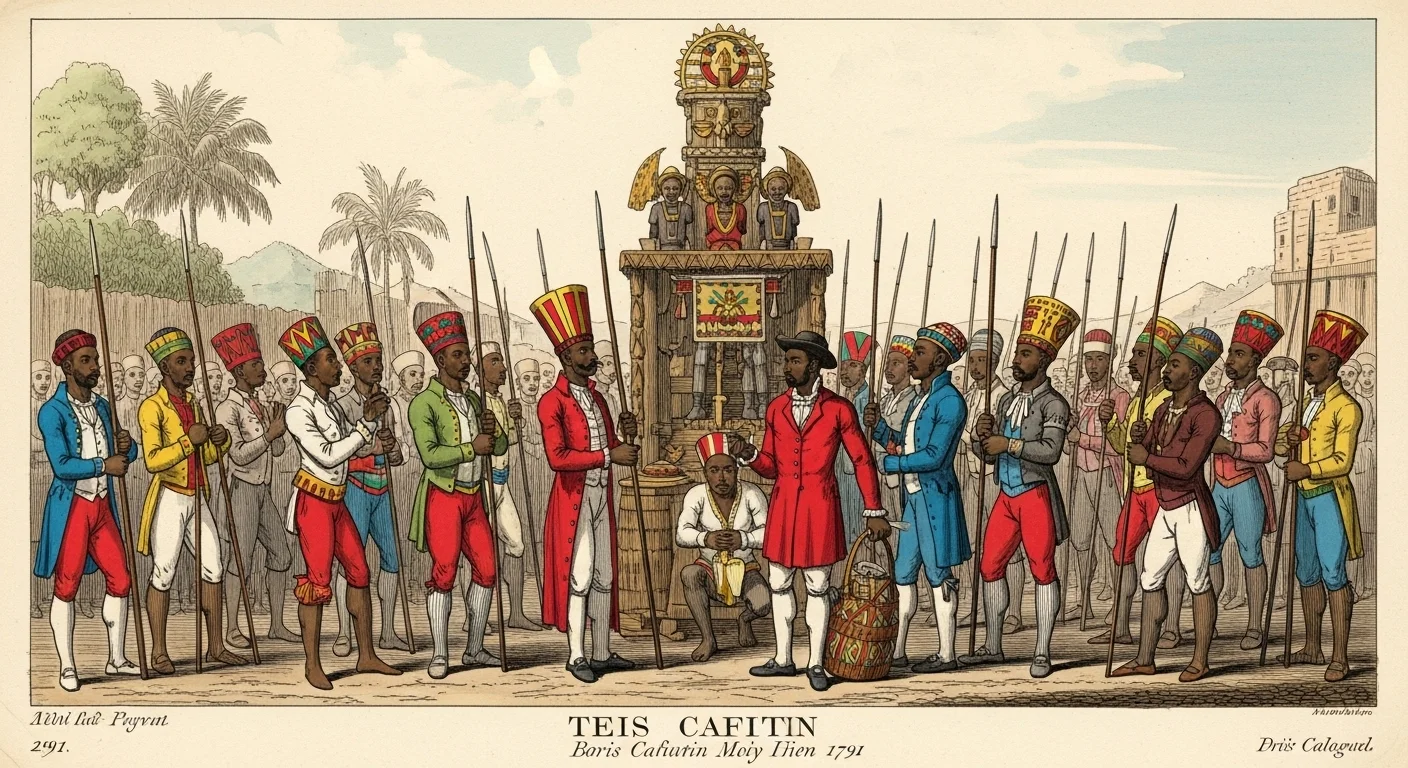

The history of vodou is inseparable from the haitian revolution. In the french colony of saint-domingue, enslaved Africans from diverse ethnic groups used their shared african religion to unite against their oppressors.

The most iconic moment occurred in 1791 at Bois Caïman. A vodou ritual led by a vodou priest and priestess ignited the flame of rebellion. This ceremony proved that vodou played a critical role in strategic organization and spiritual fortitude. Vodou and haitian independence were born together, making it the “soul” of the nation.

Throughout haitian history, despite the dominance of roman catholicism, the faith remained resilient. Vodou would eventually become the defining cultural characteristic of the haitian people, as it provided a moral and spiritual compass in the face of centuries of struggle.

Haitian Vodou Today (Diaspora Practice)

Today, the haitian diaspora in cities like New York, Miami, and Montreal keeps the faith alive. Statistics show that the Haitian-American population is approximately 1.1 million, with the largest communities in New York (approx. 190,000) and Florida (approx. 530,000). In the haitian diaspora, a vodou temple might be located in a basement or a community center, but the vodou spirits are served with the same devotion as in the countryside of Haiti.

Haitian artists and musicians in the diaspora are deeply inspired by vodou, using haitian creole and sacred rhythms to bridge the gap between their heritage and modern lives. While some confuse it with louisiana voodoo, which has its own unique evolution, haitian vodun remains a distinct, preserved tradition. As a modern form of religion, it continues to offer a sense of belonging and ethical grounding to millions.

FAQ: Haitian Vodou Questions Answered

What is Haitian Vodou?

Haitian Vodou is a monotheistic African diaspora religion that serves the lwa (spirits) and Bondye (the Creator) through ritual, music, and community service.

What is the Haitian Vodou religion?

It is a structured theological system involving a hierarchical pantheon of spirits, specific vodou ceremonies, and a commitment to ancestral healing and community protection.

What is Vodou in Haiti?

In Haiti, it is a legally recognized official religion and a cornerstone of haitian society, influencing everything from local governance to national haitian art.

Is Haitian Vodou the same as voodoo?

No. “Voodoo” is a sensationalized, pop-culture term. Haitian Vodou is the respectful and accurate name for the indigenous religion of Haiti.

Do Vodou practitioners believe in God?

Yes. Practitioners are monotheistic and believe in one supreme creator God called Bondye.

What are Lwa spirits?

Lwa are intermediary spirits in the vodou pantheon. They represent natural forces, ancestors, and archetypes who help guide the human experience.

Is Vodou evil or dangerous?

No. The idea that vodou is evil is a harmful stereotype. It is a faith rooted in healing, justice, and the survival of the haitian people.

Conclusion

What is Haitian Vodou? It is far more than a set of rituals; it is the spiritual and cultural identity of a people who fought for their freedom. By understanding the history of vodou and the vodou pantheon, we see a religion of profound resilience and beauty.

Whether practiced in a rural vodou temple in Haiti or within the haitian diaspora, this haitian religion continues to serve as a bridge between the physical world and the sacred vodou spirits.

Sources