The War of Knives, also widely discussed as the War of the South (main fighting in 1799 to 1800), was a civil war within the Haitian Revolution. It pitted Toussaint Louverture, dominant in the North and West, against Andre Rigaud, who held much of the South and its port networks.

After slavery was abolished, both leaders claimed they were defending emancipation and republican order, but they competed over who would command the army, collect revenues, and speak for Saint-Domingue in foreign diplomacy.

The conflict escalated from clashes around key routes and towns into a grinding southern campaign that ended with the fall of Jacmel in March 1800 and Rigaud’s exile, leaving Toussaint the colony’s strongest ruler before Napoleon’s expedition arrived.

Key Takeaways

- The War of Knives (often treated as the War of the South) was a revolutionary civil war in 1799 to 1800, fought for control of post-abolition Saint-Domingue.

- Toussaint sought a single chain of command, unified taxation, and centralized diplomacy; Rigaud fought to preserve southern autonomy, offices, and port-based influence.

- Race, class, and region shaped loyalties, but the conflict was also about territorial power and state-building, not only identity.

- Foreign pressures mattered. During the Quasi-War, the United States cooperated with Toussaint in ways that constrained Rigaud’s coastal position, including naval activity around the Jacmel siege.

- The war unified territory under Toussaint, but it also deepened mistrust and consumed resources shortly before Napoleon tried to reassert French control.

War of Knives (1799 to 1800): What Happened and Why It Matters

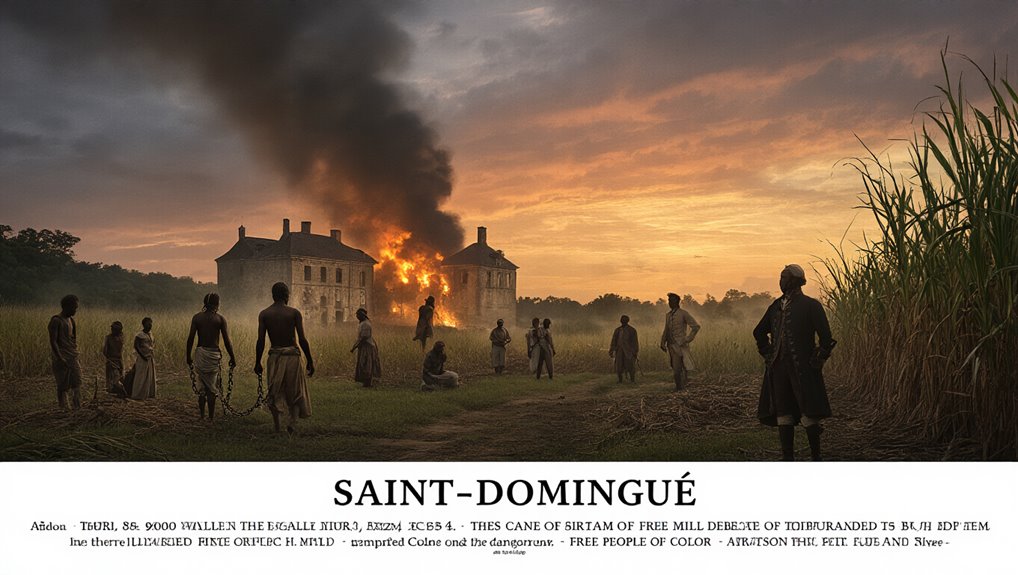

Why did allies in the Haitian Revolution turn their blades on each other? In 1799 to 1800, Saint-Domingue’s post-abolition power struggle hardened rival armies into enemies. Toussaint Louverture pushed for island-wide command after years of war, while Andre Rigaud maintained a separate southern force rooted in urban networks, port revenue, and the political ambitions of gens de couleur libres (free people of color).

Fighting spread across the Southern Peninsula and along the routes that fed the ports. The conflict ended when Toussaint’s forces captured Jacmel in March 1800, breaking Rigaud’s position and accelerating his exile.

The civil war unified territory, but it also drained strength before Napoleon’s expedition, reshaping the revolution’s path toward centralized rule and eventual independence. For how political authority later hardened into a new state, see this related discussion of political consolidation.

Why the War of Knives Split Toussaint and Rigaud

How did two leaders who fought under the same revolutionary banner come to treat each other as existential threats? After emancipation, power depended on who controlled troops, ports, taxes, and appointments.

Toussaint argued that rival commands invited foreign return and sabotage, so he pressed for a single chain of command and unified diplomacy. Rigaud feared being absorbed into a northern-centered project that would reduce southern autonomy, reshape officer ranks, and weaken the political position his coalition already held.

French officials also worsened tensions. In the late 1790s, metropolitan agents sent mixed signals and, at times, encouraged competition by favoring one leader over the other, turning suspicion into a decision for war. For broader context on governance struggles inside the revolution, see colonial governance.

Race, Class, and Region in the War of Knives

Where did the War of Knives’ bitterness come from? The conflict drew energy from race, class, and region, but it also reflected competing visions of authority after slavery ended. Toussaint’s base included many formerly enslaved Black soldiers and northern plantation districts where emancipation intensified demands for security and recognition.

Rigaud drew strength from gens de couleur libres, property holders, and southern port communities whose influence in offices, trade, and military rank felt threatened by northern domination. Regional loyalties hardened these divides.

The North’s revolutionary army culture clashed with the South’s urban networks and autonomous command. Many historians stress that this was not only an identity conflict, but a struggle over territorial and political power inside a collapsing colonial order. For a wider Atlantic frame, see Atlantic context.

How Did the War of Knives Begin in 1799?

Two forces pushed Saint-Domingue into civil war in June 1799: Toussaint Louverture’s drive to unify command across the colony and Andre Rigaud’s refusal to surrender the South’s separate army and political autonomy. Control of troops, ports, and revenues determined who could govern in practice.

The first major fighting centered on southern approaches and border towns that mattered for movement and supply, and the conflict quickly widened into a sustained campaign across the Southern Peninsula. As both sides accused the other of betrayal and foreign intrigue, compromise collapsed and war became the method for deciding legitimacy.

France and Foreign Powers in the War of Knives

The War of Knives did not unfold in isolation. France’s uncertain direction after the French Revolution left room for local agents to maneuver, while rival empires watched for openings. The broader Atlantic war environment shaped legitimacy, arms access, and trade.

Most importantly, during the Quasi-War era, the United States found it strategically useful to work with Toussaint against forces viewed as closer to French influence. That alignment showed up most clearly at sea.

U.S. naval activity supported operations around the southern coastline, and American cooperation helped tighten pressure during the long siege that ended at Jacmel. If you want a larger timeline view of foreign intervention and shifting alliances, see Britain’s intervention and related phases of the war.

Major Battles, Sieges, and Logistics (1799 to 1800)

The War of Knives was decided through roads, ports, and endurance as much as battlefield shock. The fighting concentrated on controlling movement between towns, holding coastal access, and denying opponents the ability to feed and supply forces for months at a time.

Opening Campaigns (Summer 1799)

The first phase turned on southern border towns and the routes toward Port-au-Prince. Early victories strengthened Rigaud’s confidence and forced Toussaint to treat the South as a full-scale rival power, not a subordinate command.

The Siege of Jacmel (Late 1799 to March 1800)

The war’s defining struggle became the siege of Jacmel, a strategic port and a symbol of southern resistance. Fighting dragged on for months as attackers tightened land pressure and naval forces constrained the coastline.

Contemporary accounts and later histories note that U.S. naval support was present during the siege, including fire support as Toussaint’s forces pressed the city. The fall of Jacmel in March 1800 broke the southern network and accelerated Rigaud’s decision to flee into exile.

Collapse and Exile (1800)

After Jacmel fell, remaining southern positions weakened as commanders reassessed loyalty, manpower, and supply. The war did not end in a single moment everywhere, but Rigaud’s ability to govern militarily collapsed over weeks. With the South fracturing and the ports increasingly vulnerable, exile became the only viable option for Rigaud and many of his closest officers.

How Did Toussaint Win, and What Happened to Rigaud?

Toussaint Louverture won by combining pressure, logistics, and coalition management. He moved veteran forces through key corridors, kept commanders focused on isolating strongholds, and used coastal constraint to make southern ports increasingly difficult to sustain.

The siege of Jacmel became decisive because it linked land pressure to maritime constraint, and U.S. naval activity supported the tightening noose during the Quasi-War era. After defeat, Rigaud chose exile and sailed to France, sidelining a major rival faction and leaving Toussaint dominant across Saint-Domingue. For the larger argument about governance and centralization under Toussaint, see state-building.

How Did the War of Knives Shape Haitian Independence?

By the time Jacmel fell and Rigaud was forced out, the War of Knives had already reshaped the revolution’s road toward independence. Toussaint’s victory settled who could claim island-wide authority, enabling a more centralized administration and the political steps that followed, including the 1801 constitution that reaffirmed abolition while concentrating power.

At the same time, the civil war consumed resources, hardened mistrust, and created wounds that did not disappear. Those vulnerabilities mattered when Napoleon attempted to reassert control in 1802. In that sense, the War of Knives both unified the colony and weakened it, setting the stage for the next phase of conflict that ultimately ended in Haitian independence.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Were Toussaint Louverture and Andre Rigaud’s Early Lives Like?

Toussaint Louverture was born enslaved (often dated to the early 1740s), later gained freedom, and rose during the revolution into the colony’s most powerful commander. Andre Rigaud was a leading southern general associated with free people of color communities and southern port society, rising into prominence through local military and political struggles in Saint-Domingue.

How Many Soldiers Fought, and What Were Casualty Estimates?

Estimates vary widely because records are incomplete and often politicized. Some summaries suggest large forces mobilized on both sides, but firm casualty totals are difficult to prove. A careful approach is to describe the war’s intensity and disruption while acknowledging that precise numbers remain contested.

What Role Did Women Play During the War of Knives?

Women supported the war effort in many ways that sources often undercount: as messengers, market networks, nurses, intelligence carriers, and household organizers who kept food moving and families alive during sieges and raids. Their labor helped sustain both armies and civilian communities through prolonged disruption.

How Did the Conflict Affect Everyday Life for Civilians?

The war upended daily life. Civilians faced raids, forced requisitions, displacement, food shortages, and port disruption that damaged trade and local markets. Many rural workers, recently emancipated, still lived under harsh military labor systems and could be pressed into service, moved by commanders, or caught between rival authorities.

Where Can Visitors See War of Knives Sites or Artifacts Today?

In Haiti, visitors can look for material culture and national history exhibits at the Musee du Pantheon National (MUPANAH) in Port-au-Prince. Jacmel remains an important place to understand the war’s geography, although many specific sites are not formally interpreted on the ground. Archival documents are split across repositories in Haiti, France, and other collections connected to the Atlantic world.

Conclusion

The War of Knives exposed deep fractures in revolutionary Saint-Domingue as Toussaint Louverture and Andre Rigaud fought over authority, regional autonomy, and competing social coalitions after slavery was abolished. Foreign pressures shaped the battlefield, and the long struggle for ports and routes culminated in Jacmel’s fall and Rigaud’s exile.

Toussaint’s victory unified territory and strengthened central rule, but the civil war also deepened mistrust and consumed strength on the eve of Napoleon’s attempt to reconquer the colony. Understanding this conflict helps explain why unity, coercion, and legitimacy became such urgent questions on the road to Haitian independence.

References

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Haitian-Revolution

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/War_of_the_South

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/25061898

- https://ussconstitutionmuseum.org/major_timeline/james-sever-arrives-in-saint-domingue/

- https://today.duke.edu/2015/07/haiti

- https://www.biography.com/political-figures/toussaint-louverture

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Toussaint-Louverture