Voodoo, often referred to academically and culturally as Vodou, is a profound spiritual system with roots deep in West African history. It evolved significantly as it crossed the Atlantic to the Caribbean, particularly Haiti, and the American South, most notably Louisiana.

Far from the sensationalized depictions in popular media, it is a religion centered on community, ancestry, and the balance of natural forces.

At the heart of this tradition lies a complex hierarchy of spiritual entities known as the Lwa or Loa. These spirits serve as intermediaries between humanity and the supreme creator, often referred to as Bondye. The names associated with these spirits, as well as the names given to practitioners, carry immense weight and significance.

Understanding Voodoo names requires looking beyond simple labels to see the history and energy they represent. Whether referring to the divine pantheon or the names bestowed upon initiates, each title serves as a key to unlocking specific spiritual attributes. This guide explores the rich tapestry of names, figures, and meanings that define this enduring faith.

The Cultural Origins of Voodoo Naming Traditions

The naming conventions within Voodoo are deeply rooted in the linguistic and cultural traditions of West Africa. Much of the terminology stems from the Fon, Ewe, and Yoruba peoples of present-day Benin and Nigeria. When enslaved Africans were brought to the New World, they preserved their heritage by retaining the names of their deities and ancestors.

In the diaspora, these African traditions merged with elements of Roman Catholicism and indigenous beliefs, a process known as religious syncretism. This fusion created a unique spiritual landscape where African spirits were often associated with Catholic saints to hide traditional worship from colonial authorities.

Consequently, the names used in Voodoo often reflect this dual heritage, carrying meanings that bridge two distinct worlds.

Names in this tradition are not merely identifiers; they are viewed as vessels of power and destiny. In many West African cultures, a name can determine a child’s character, social role, and spiritual path. This belief persisted in the Americas, where knowing the true name of a spirit or a person is considered essential for establishing a genuine spiritual connection.

Understanding the Lwa: The Spirits Behind the Names

The Lwa are the central figures of worship in Voodoo, distinct from the distant creator god. They are accessible, relatable, and possess distinct personalities, preferences, and domains of influence. Practitioners, often called serviteurs, build relationships with these spirits through prayer, offerings, and specific rituals.

The Lwa are generally divided into different “nations” or families, known as nanchon. The two most prominent nations are the Rada and the Petro. The Rada spirits are associated with coolness, water, and patience, tracing their lineage directly to Dahomey in West Africa. Their names often evoke a sense of ancient wisdom and stability.

In contrast, the Petro spirits are considered “hot,” fiery, and aggressive. Born from the harsh realities of slavery and the struggle for independence in Haiti, these spirits demand quick action and strict discipline. Understanding which nation a spirit belongs to is crucial for interpreting the meaning and energy behind their name.

Major Spirits and Their Associated Names

The Voodoo pantheon is vast, but several key figures appear frequently in rituals and cultural references. Their names are invoked to request specific blessings, guidance, or protection. Each spirit represents a fundamental aspect of the human experience or the natural world.

Papa Legba: The Guardian of the Crossroads

Papa Legba is the first spirit invoked in any ceremony because he holds the keys to the spiritual gate. Without his permission, communication with the other Lwa is impossible. He is associated with St.

Peter or St. Lazarus and represents opportunity, communication, and the opening of paths.

Baron Samedi: The Master of the Cemetery

As the head of the Guede family, Baron Samedi governs death, regeneration, and ancestry. Despite his association with death, he is also a figure of life, humor, and sexuality. His name commands respect for the cycle of life and the inevitability of transition.

Erzulie Freda: The Spirit of Love and Luxury

Erzulie Freda is the Rada Lwa of romantic love, beauty, and abundance. She is often envisioned as a wealthy, elegant woman who loves jewelry and fine perfumes. Her name is synonymous with the pursuit of beauty and the emotional depth of the human heart.

Ogun (Ogou): The Warrior of Iron

Ogun is a powerful spirit associated with fire, iron, war, and technology. He is the patron of soldiers, blacksmiths, and anyone who works with metal. His name invokes strength, protection, and the drive to overcome obstacles through force and determination.

Damballah Wedo: The Sky Father

Depicted as a great white serpent, Damballah is one of the oldest and most revered Rada spirits. He represents creation, peace, and wisdom. His presence is said to bring a profound calm, and his name is called upon for purification and clarity.

Naming Ceremonies and Spiritual Identity

In traditional Voodoo practice, receiving a spiritual name is a significant milestone. This often occurs during an initiation ceremony known as Kanzo. During this process, an initiate enters the Hounfour (temple) to undergo rites that deepen their connection to the spirits.

The name given during initiation is not chosen randomly. It is believed to be revealed by the spirits themselves, often through divination performed by a Houngan (priest) or Mambo (priestess). This new name reflects the initiate’s spiritual lineage and the specific Lwa that rules their head, known as the Met Tet.

This spiritual name serves as a shield and a source of identity within the religious community. It marks the transition from an outsider to a dedicated member of the society. For many, this name is held as a sacred secret, known only to the initiate and their spiritual family, to protect their energy.

Common Voodoo-Inspired Names and Meanings

While many names are reserved for initiated practitioners or spirits, the culture has influenced naming trends in regions with strong Voodoo heritage. Parents may choose names rooted in these traditions to honor their ancestry or to invite specific virtues into a child’s life. These names often carry lyrical beauty and deep historical resonance.

Names for Girls

Names like Ayizan (the spirit of the marketplace and commerce) or Erzulie are sometimes adapted. Marassa refers to the sacred twins, representing duality and balance. Loko is associated with the Lwa of vegetation and healing, symbolizing growth and natural health.

Names for Boys

Simbi is a popular name linked to the spirits of fresh water and rain, known for their intelligence and clairvoyance. Agwe refers to the sovereign of the seas, symbolizing depth and emotional command. Legba is occasionally used to denote a child who is seen as a communicator or a bridge between families.

Unisex and Family Names

Many surnames in the Caribbean and Louisiana can be traced back to these spiritual lineages. Names derived from Jean, Baptiste, or Pierre often have specific associations with Voodoo saints and spirits due to the syncretic nature of the religion. These names serve as a subtle nod to a family’s enduring faith.

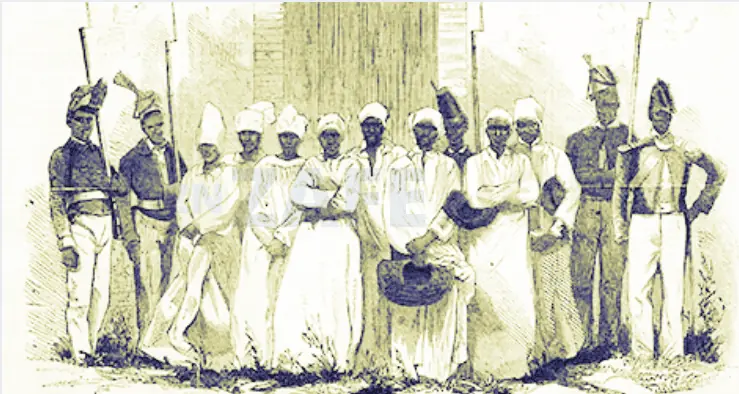

Historical Figures: The Legacy of Marie Laveau

No discussion of Voodoo names is complete without mentioning the historical figures who shaped the religion’s public image. In 19th-century New Orleans, Voodoo became a powerful social force, largely due to the influence of Marie Laveau. Known as the Voodoo Queen, she was a free woman of color who successfully navigated the racial and social divides of her time.

Marie Laveau was not just a practitioner; she was a community leader who combined Voodoo rituals with Catholic practices. She held elaborate public ceremonies on St. John’s Eve, drawing crowds from all walks of life. Her name remains legendary, symbolizing female empowerment and spiritual authority in Louisiana history.

Another significant figure was Dr. John, also known as Bayou John. He was a prominent Senegalese root doctor and Voodoo priest in New Orleans. These historical figures demonstrate how Voodoo names became intertwined with the identity of the region, representing resistance, resilience, and cultural preservation.

Misconceptions vs. Reality in Voodoo Culture

Popular culture has done a disservice to Voodoo by associating its names and practices primarily with curses, dolls, and darkness. In reality, the religion is focused on Sevis Ginen, or service to the spirits, which emphasizes healing, balance, and community support. The “Voodoo doll” is largely a fabrication of American folklore and Hollywood, bearing little resemblance to authentic practice.

When a practitioner invokes a name like Baron Samedi, it is not to cause harm, but often to help a grieving family find closure or to protect a child. The spirits are viewed as stern but loving parents who guide their children. Understanding the true meaning of these names helps dismantle the stereotypes that have long plagued this faith.

By learning the actual history and definitions behind Voodoo terminology, outsiders can gain respect for a complex theological system. It is a religion that honors the past while navigating the present. The names of the Lwa are reminders of the enduring connection between the living and the spiritual world.

FAQ

What is the difference between Voodoo and Hoodoo?

Voodoo (Vodou) is an initiated religion with a structured theology, clergy (Houngans and Mambos), and specific deities (Lwa). It originated in West Africa and developed in Haiti. Hoodoo, on the other hand, is a system of African American folk magic and rootwork that developed in the Southern United States. While Hoodoo incorporates some Voodoo elements, it is not a religion and does not typically involve a hierarchy of clergy or temples.

Is Voodoo considered a closed practice?

Voodoo is generally considered an initiatory religion, meaning that full participation in its deeper rituals requires guidance from an established priest or priestess. While anyone can learn about the history and respect the Lwa, specific ceremonies and the authority to perform rituals are reserved for those who have undergone initiation.

This structure ensures that the traditions are preserved accurately and respectfully.

What is a Veve in Voodoo tradition?

A Veve is a religious symbol used in rituals to call upon a specific Lwa. These intricate geometric designs are usually drawn on the ground using cornmeal, flour, or other powders. Each spirit has their own unique Veve, which acts as a beacon for their energy. The drawing of the Veve is a meditative and sacred act performed by the priest or priestess during a ceremony.

Can anyone use Voodoo names for their children?

While there are no laws against using these names, it is important to understand their cultural and spiritual weight. Names like Erzulie or Legba are directly tied to powerful deities. In the cultures where Voodoo is practiced, these names are treated with great reverence. Using them without understanding their significance can be seen as culturally insensitive or spiritually presumptuous by practitioners.

Do Voodoo dolls actually exist in the religion?

The concept of the “Voodoo doll” used to inflict pain is largely a myth created by fiction and movies. In authentic practice, dolls or figures may be placed on altars to represent spirits or ancestors, but they are used for healing, communication, or focusing energy. They are not tools for revenge or harm, as is commonly depicted in pop culture.

What is the role of ancestors in Voodoo?

Ancestors are the foundation of Voodoo spiritual life. Before addressing the Lwa, practitioners often honor their ancestors, known as “Les Morts.” It is believed that the ancestors provide the wisdom and foundation for the living. Maintaining a connection with one’s lineage is considered essential for spiritual health and personal stability.