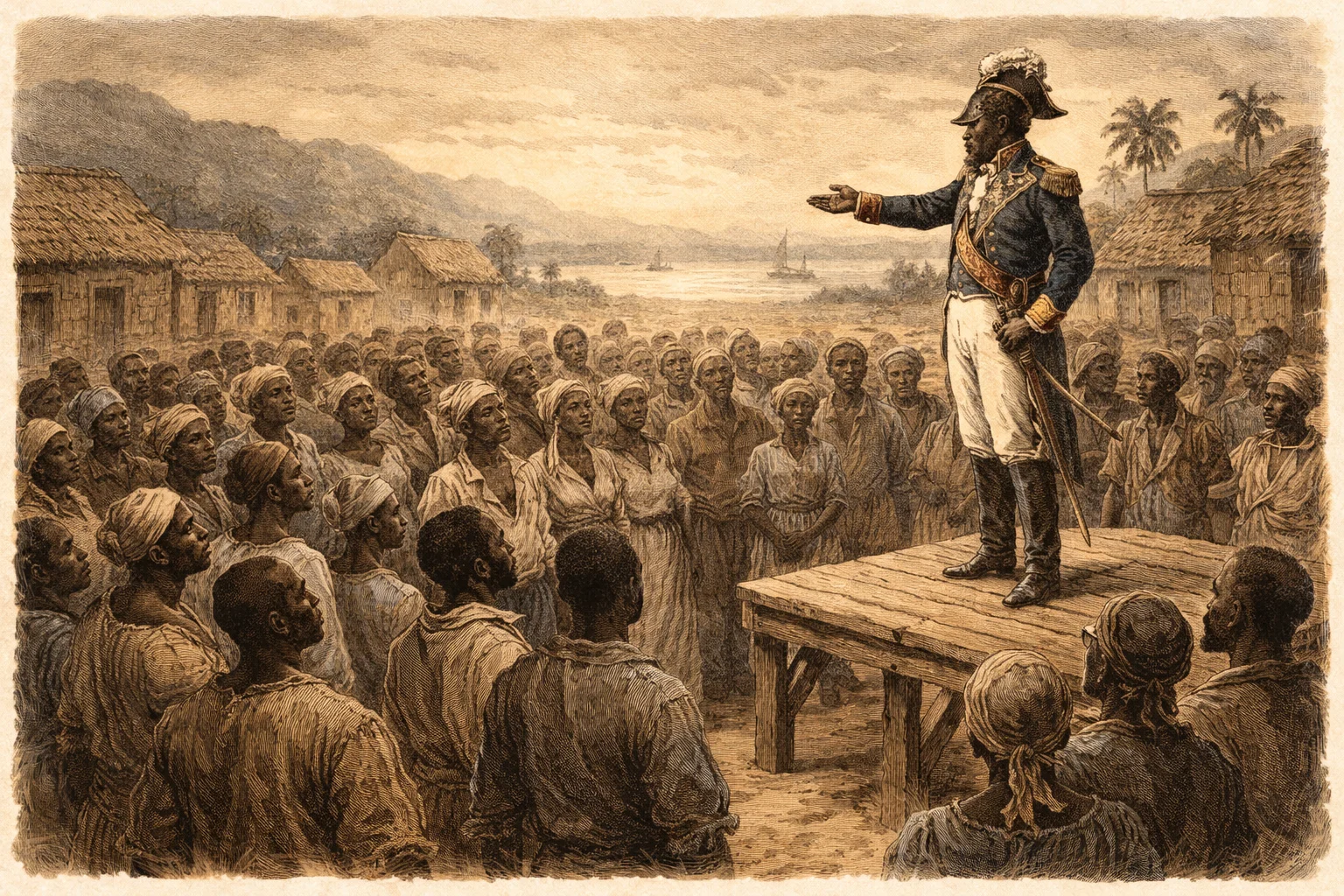

On January 1, 1804, in Gonaïves, Jean-Jacques Dessalines publicly proclaimed Haiti’s independence from France. The declaration was drafted by his secretary, Louis Boisrond-Tonnerre, and it framed independence as a permanent break backed by a collective vow to resist any return of French rule. (Encyclopedia Virginia, primary document)

This page explains what the proclamation said, why it was written the way it was, and how to read it in the context of the final military phase of the Haitian Revolution in 1803 to 1804. It also clarifies what came later, including France’s 1825 recognition and the United States’ 1862 recognition, so those milestones are not confused with independence itself. (Office of the Historian)

What Haiti’s declaration of independence meant in 1804

The declaration did two things at once. First, it announced a political reality: France had been defeated in the final phase of the war, and a new state would govern itself. Second, it tried to make reversal impossible by turning independence into a sworn commitment. In the text, the generals are described as taking a vow to “forever renounce France” and to fight rather than submit to renewed domination. (Duke Today, declaration text)

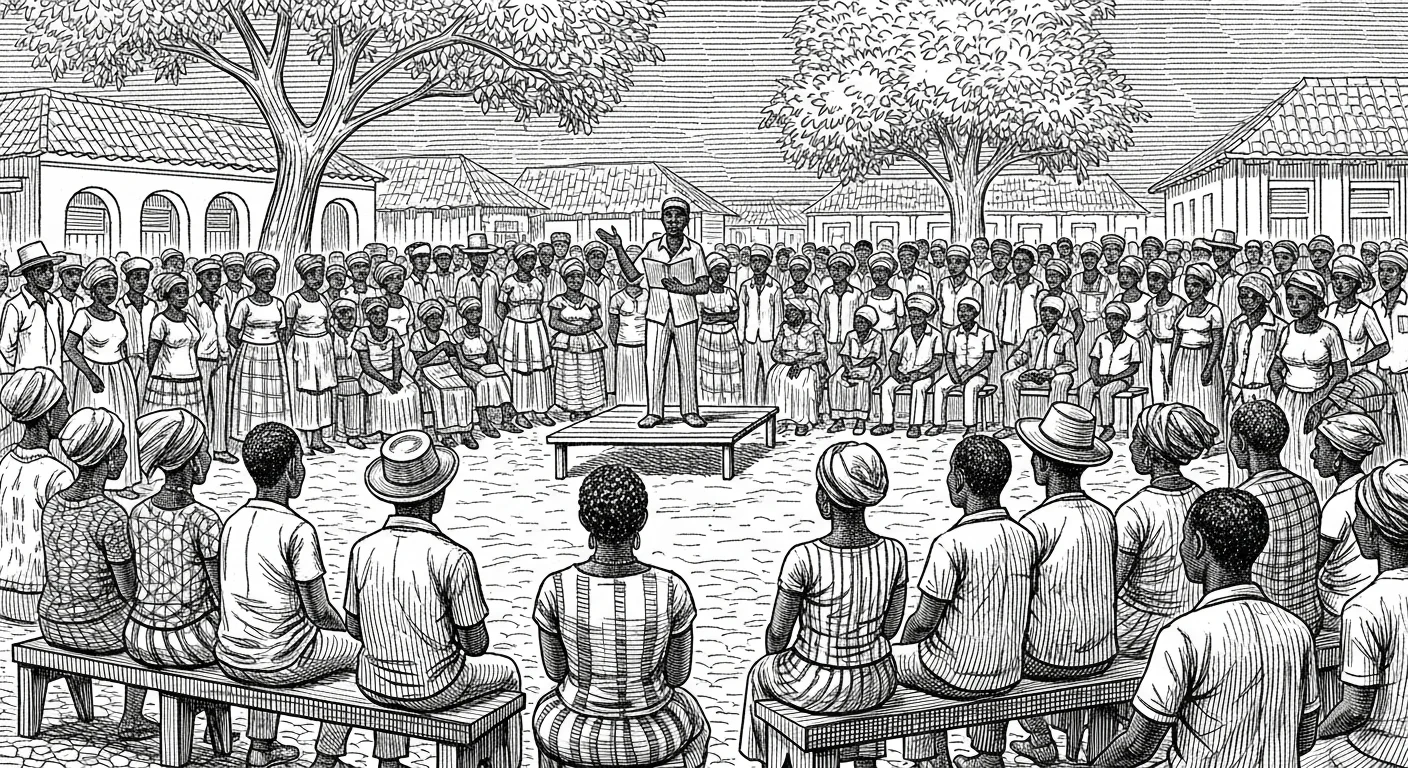

That “no return” posture matters because the declaration was not only a message for Haitians in Gonaïves. Historian Philippe R. Girard argues it was a layered document aimed at multiple audiences, including foreign governments that might consider intervention or non-recognition. (OUPblog, Girard)

Jean-Jacques Dessalines before independence (1791 to 1804)

Dessalines emerged as a leading commander during the Haitian Revolution’s shifting alliances and brutal escalation after the 1791 uprising in Saint-Domingue. By the early 1800s, he was one of the central military figures resisting Napoleon’s attempt to restore French authority, and he became the leading figure at the moment of independence in 1804. (Britannica, Dessalines biography)

It is also important to separate roles: Dessalines was the political and military leader whose authority anchored the proclamation, while Boisrond-Tonnerre is credited with drafting the text itself. (Encyclopedia Virginia, authorship note)

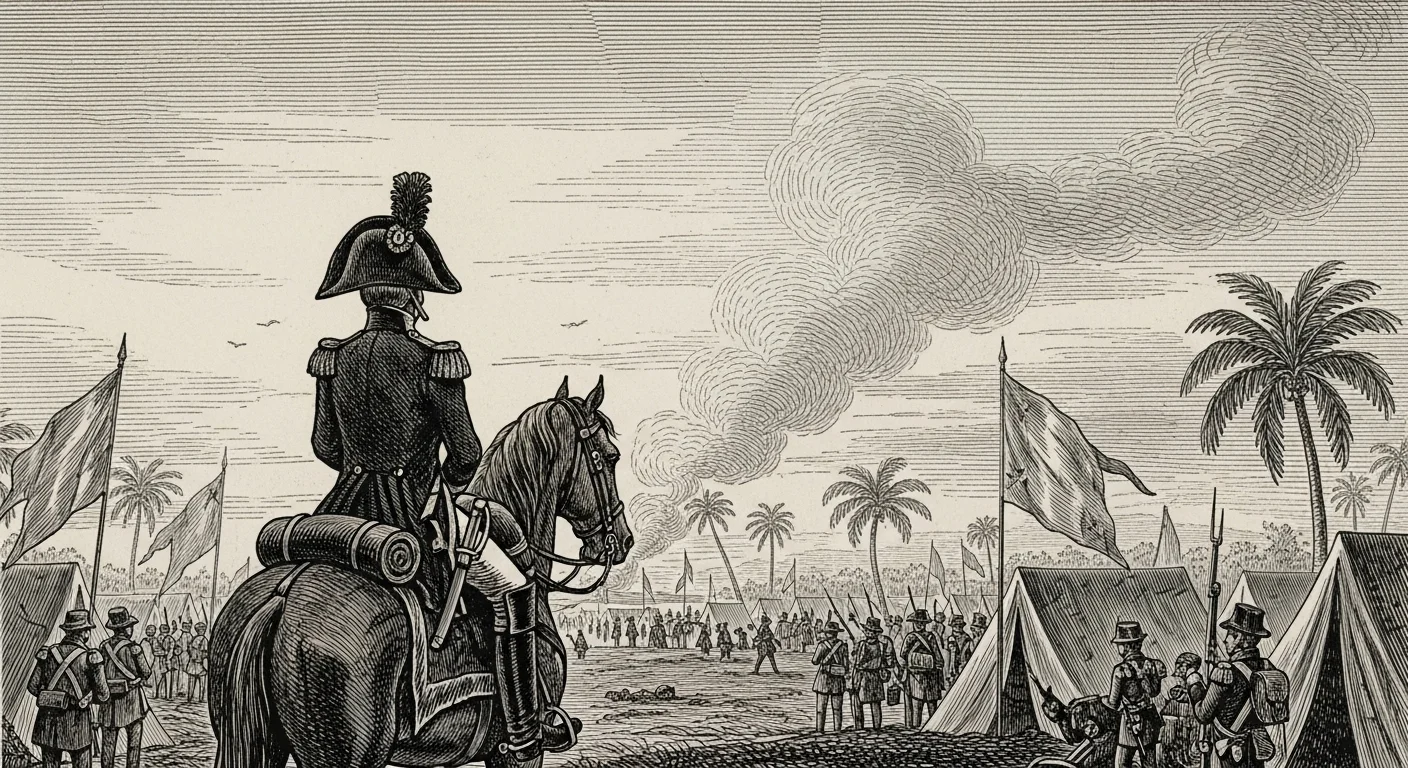

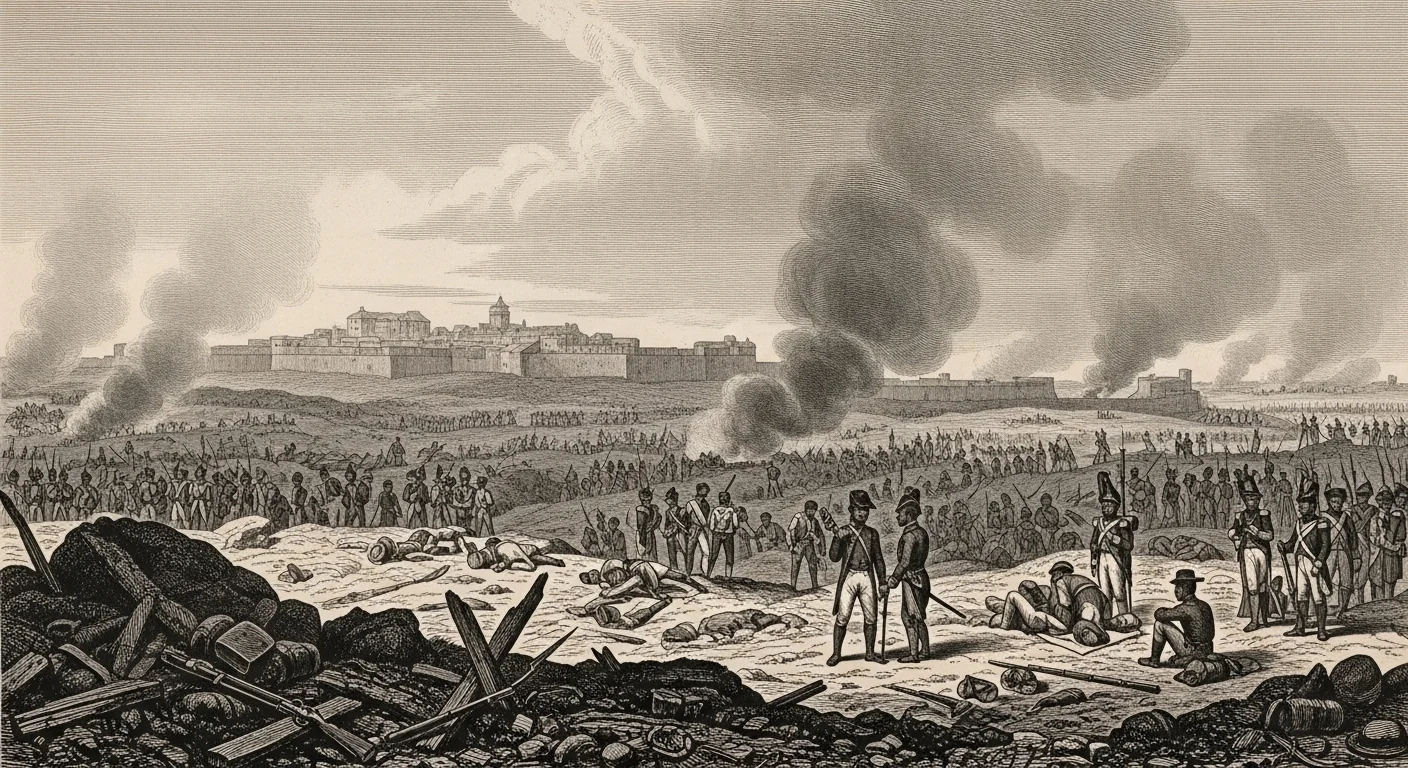

From Vertières to January 1, 1804 … the final break with France

The declaration comes after the French expedition’s defeat in late 1803, including the Battle of Vertières, and it marks the political conclusion of that military outcome. (Britannica, Haitian Revolution) In other words, it does not describe a future hope. It formalizes what the war’s final phase had already made true: France would not be governing Saint-Domingue again.

For readers, this is the key timeline distinction: Haiti declared independence in 1804; later diplomatic milestones are separate events with different labels and consequences. The United States Department of State’s historical overview explicitly treats France’s 1825 recognition and the United States’ 1862 recognition as later steps, not the moment independence occurred. (Office of the Historian)

What the proclamation says … tone, audiences, and political goals

The declaration is often remembered for its defiant framing, including the famous opening formula “Independence or death.” (Encyclopedia Virginia, text) In the Duke collection’s presentation of the “Deed of Independence,” the document emphasizes renouncing France and defending independence “until their last breath,” which is a political promise as much as a rhetorical flourish. (Duke Today, declaration text)

Girard’s reading helps explain the document’s style: it was written in formal French, which made it legible to foreign officials and elites, even if many listeners in 1804 used French as a second or third language. (OUPblog, Girard) That choice supports a practical goal: warn France and signal resolve to other powers watching Haiti’s emergence.

Social context in Saint-Domingue … revolution and plantation society

Saint-Domingue was a plantation colony structured around coerced labor, racial hierarchy, and export wealth, and the revolution’s stakes were inseparable from that system. A declaration of independence here was not just a transfer of flags. It was a refusal of a social order built on slavery and enforced by colonial violence. (Britannica, Haitian Revolution)

Reading the proclamation alongside the revolution’s trajectory also clarifies why its language emphasizes permanent separation and collective defense. The fear was not abstract. Napoleon’s expedition had been sent to restore French control, and contemporaries understood that “restoration” could mean the return of slavery. (Office of the Historian)

International reactions after 1804 … what changed and what did not

Independence did not automatically bring diplomatic recognition. France formally recognized Haitian independence in 1825, while the United States waited until 1862 to recognize Haiti as a sovereign state. (Office of the Historian) These are recognition milestones, not independence dates.

The 1825 recognition is also tied to coercive financial terms that burdened Haiti for generations. Scholarship on the “independence debt” links recognition to an imposed indemnity framework that Haiti and many historians describe as extracted under threat. (Oosterlinck et al., SSRN working paper) For a concise reference overview, Britannica also summarizes that recognition came with an indemnity that Haiti agreed to pay. (Britannica, Haiti: The Haitian Revolution)

Legacy and historical debate … how historians interpret Dessalines

Dessalines’s legacy is debated because independence did not end political conflict. Within the same year as the declaration, he assumed the title of Emperor Jacques I, and he was killed in 1806 amid internal struggles. (Britannica, Dessalines biography) Some interpretations emphasize him as the indispensable military leader of independence; others emphasize the authoritarian turn and the difficult realities of governing under diplomatic isolation.

One practical way to keep the debate grounded is to separate (1) the declaration as a wartime political act and (2) the governing choices that followed once Haiti faced non-recognition, economic pressure, and internal division. The Cambridge History of the Age of Atlantic Revolutions frames the decades after 1804 as a contested post-colonial process of building a Black nation-state in a world still dominated by racialized slavery. (Cambridge Core)

Frequently Asked Questions

What was Jean-Jacques Dessalines’s role during the Haitian War for Independence?

Dessalines was a principal military leader in the final phase of the Haitian Revolution and the leading figure who proclaimed independence in 1804. (Britannica, Dessalines biography) The proclamation delivered on January 1, 1804, is associated with his leadership, while the text itself is attributed to his secretary, Louis Boisrond-Tonnerre. (Encyclopedia Virginia)

Who wrote the Haitian Declaration of Independence?

Multiple reputable references credit Louis Boisrond-Tonnerre, Dessalines’s secretary, as the author of the declaration text. (Encyclopedia Virginia, authorship note) Dessalines’s role was leadership and public proclamation at the moment of independence. (Britannica, Haitian Revolution)

What did the declaration actually say, in plain terms?

In plain terms, it announces a permanent break with France, frames independence as a collective commitment, and warns that any attempt to restore French domination will be resisted. You can read an English translation and contextual notes in the Encyclopedia Virginia primary document entry. (Encyclopedia Virginia, text)

Why do some sources say recognition came later, in 1825 or 1862?

Because “recognition” is a diplomatic act by other states, not the same thing as declaring independence. The United States Department of State’s historical overview treats France’s 1825 recognition and the United States’ 1862 recognition as later diplomatic milestones after independence had already been declared and defended. (Office of the Historian)

How this page was prepared … and where to read the original documents

This explainer was written by cross-checking (1) accessible translations of the January 1, 1804 declaration, (2) archival holdings and surviving copies documented in major collections, and (3) reference syntheses that summarize the revolution and the recognition timeline. For readers who want the closest view of the declaration as a document, the UK National Archives catalog entry provides a digitized reference point, and Duke’s project pages explain how surviving copies were rediscovered and studied. (UK National Archives) (Duke Today)

Sources

- Encyclopedia Virginia: “The Haitian Declaration of Independence (January 1, 1804)” (translation + context)

- Duke Today: “Rediscovering Haiti’s Declaration of Independence” (text and project context)

- Duke Digital Repository: “Haitian Declaration of Independence” (manuscript copy record)

- UK National Archives: “Haitian Declaration of Independence” (catalog entry)

- U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian: “The United States and the Haitian Revolution, 1791 to 1804”

- Britannica: “Jean-Jacques Dessalines”

Conclusion

Haiti’s declaration of independence is best read as both a political announcement and a binding commitment, made after a decisive military victory and aimed at audiences inside and outside the new nation.

The text ties independence to an irreversible renunciation of France and to a collective duty to defend sovereignty. (Duke Today) What came after … delayed recognition, imposed pressures, and internal conflict … shaped Haiti’s early decades, but it does not change what happened in Gonaïves on January 1, 1804: the public act of declaring independence and claiming self-rule.