Haitian Vodou is a decentralized Afro-Caribbean religion that formed in Haiti through the blending of West and Central African traditions under French colonial rule, often practiced alongside Catholicism.

Bondye is the distant creator, while lwa serve as approachable intermediaries honored through sevis lwa, prayer, drumming, dance, offerings, and sometimes possession trance. Ceremonies in an ounfò use veves, altars, and sacred objects to guide worship and healing, countering sensational myths that miscast Vodou as sinister. There’s much more to uncover ahead.

Key Takeaways

- Haitian Vodou is a decentralized Afro-Caribbean religion formed in Haiti through creolized West and Central African traditions under French colonial rule.

- Bondye is the distant creator; practitioners serve lwa as intermediaries through sevis lwa, prayer, drumming, dance, and spirit possession.

- Vodou often coexists with Catholicism, shaped by Code Noir and saint-lwa pairings rather than simple “syncretism” or disguise.

- Ceremonies in an ounfò use veves, altars, songs, and ritual objects; offerings can include animal sacrifice with shared meat strengthening community bonds.

- Popular media misrepresents Vodou as sinister; in reality it centers ancestors, healing, justice, solidarity, and Haitian history and resilience.

What Haitian Vodou Is (and Isn’t)

So what’s Haitian Vodou—and what isn’t it? It’s a decentralized Afro-Caribbean religion formed in Haiti through creolization of Fon, Yoruba, Kongo, and Dahomey traditions under French colonial rule. Because the Code Noir repressed African worship, practitioners aligned lwa with Catholic saints, often practicing alongside Catholicism without contradiction.

Vodou centers on Bondye as a distant creator and the lwa as intermediaries served through sevis lwa, prayer, drumming, possession trance, and offerings, including animal sacrifice whose meat is shared.

It emphasizes ancestors, communal ethics, justice, and solidarity, a perspective that is supported by Resources on the Atlantic World and slave-era histories that contextualize how religious practices persisted and transformed under colonial systems. Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database

Haitian Vodou Myths vs. Reality (Zombies, “Magic”)

Sensational travelogues, horror films, and colonial-era propaganda turned a living religion into spectacle, framing its ceremonies as sinister rather than sacred.

In addition, scholarly and archival resources show that Haitian Vodou is a complex, community-centered practice deeply intertwined with history, memory, and resilience. Haitian history resources

Haitian Vodou Roots in Africa and Haiti

Seeing Vodou as more than spooky folklore means tracing where it actually comes from: a meeting of West and Central African religions—Fon, Yoruba, Kongo, and Dahomey royal traditions—with the brutal realities of French colonial Saint-Domingue.

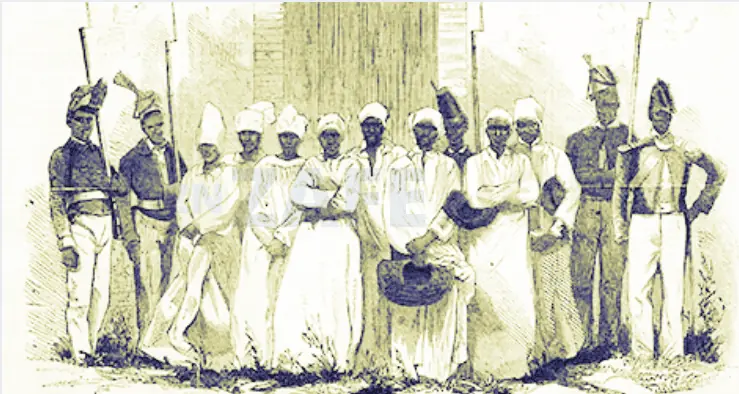

Between the 16th and 19th centuries, captives carried sacred songs, rites, and cosmologies into plantations, where creolization on Hispaniola fused languages and lineages into a new Haitian religion by the mid-1700s. Under the Code Noir, banned African worship adapted through Catholic cover, pairing spirits with saints.

Vodou’s public emergence shaped collective resistance, echoing in the Bois Caïman catalyst of 1791. The revolutionary context demonstrates how enslaved and free communities navigated power, faith, and identity within a changing political landscape. Bois Caïman

Bondye and the Lwa: How Vodou Works

How does Vodou “work” in daily spiritual life? Practitioners see Bondye as the supreme creator, yet distant and not directly petitioned.

In addition to sevis lwa and the interplay with Catholic saints, communities may engage in roundtable-style discussions and study that explore the historical roots of Vodou within Haitian religious practice and memory, such as the way ritual performance and lineage connect to broader continuities in Haitian history and culture. roundtable-style discussions

The Soul and Afterlife in Haitian Vodou

Death doesn’t sever relationships; it reshapes them into obligations of remembrance and respect. In Haitian Vodou, the dead are connected to communities through ancestral lines and the land, which helps maintain moral order and mutual aid across generations.

The living are called to honor these bonds, and neglect can invite imbalance or misfortune ancestor veneration. Over time, the spirit’s lingering aspect is guided toward its rightful place, supporting harmony between the visible and invisible worlds.

What Happens in a Vodou Ceremony

What actually happens when a Vodou ceremony begins? Participants gather in an ounfò, greet elders, and open with prayers that honor Bondye while calling the loa as intermediaries. Drummers set specific rhythms, singers respond in call-and-response, and dancers move in patterned steps that build spiritual focus.

A mambo or houngan leads invocations, blesses attendees, and guides communal intentions like healing, protection, or reconciliation. As intensity rises, a loa may “mount” someone in trance; the possessed person gives counsel, accepts offerings, and may prescribe remedies. When animals are sacrificed, meat’s shared, reinforcing solidarity. Haitian Vodou Practices

Veves, Altars, and Sacred Objects in Vodou

Inside an ounfò, veves, altars, and sacred objects aren’t decoration—they’re the practical “language” Vodou uses to welcome the loa and focus a community’s intent. Veves are precise floor drawings, traced in cornmeal or ash, that mark which spirit’s being served and where it’s invited to arrive.

Altars gather candles, water, rum, food, and saint images that mirror the loa through Catholic syncretism. Sacred objects—bells, rattles, drums, machetes, flags, and stones—carry histories, vows, and ancestral presence. Handled correctly, they align rhythm, offering, and prayer so possession and healing can unfold safely. Primary sources provide historical context for how these practices have circulated and transformed across communities over time.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Do You Find a Reputable Houngan or Mambo Outside Haiti?

They’ll find a reputable houngan or mambo by seeking referrals from established Haitian communities, verifying lineage and community standing, attending public services, avoiding fee-heavy “instant initiation” claims, and prioritizing respectful, consent-based sevis lwa practice.

Is Haitian Vodou Officially Recognized or Protected by Haitian Law?

Yes—Haitian law officially recognizes Vodou; it’s been an official religion since a 2003 decree under President Aristide. Protection isn’t always consistent, though, and practitioners’ve still faced social and institutional harassment.

Can Non-Haitians Be Initiated, and What Are the Requirements?

Yes—non-Haitians can be initiated, but it’s community-led and varies. They’ll need a reputable houngan/mambo, sustained participation, ethical conduct, fees and offerings, and consent from the lwa through divination and ceremony.

What Ethical Guidelines Govern Animal Sacrifice and Ritual Offerings Today?

Today, communities say sacrifices must be respectful, necessary, and community-serving: animals are well cared for, killed quickly, offerings shared, and rituals led by initiated clergy. They’ll follow local laws and avoid coercion or waste.

How Does Vodou Interact With Modern Medicine and Mental Health Care?

Vodou often complements modern care: many practitioners’ll consult doctors while seeking lwa service for meaning, protection, and community support. Some healers interpret distress spiritually, so culturally competent clinicians coordinate, screen for illness, respect rituals, and avoid stigma.

Conclusion

Haitian Vodou emerges as a living spiritual tradition, not a horror trope or “dark magic.” Rooted in West and Central African religions and shaped in Haiti, it centers on Bondye and the lwa, honoring ancestors and community through prayer, song, and ritual.

Ceremonies, veves, altars, and sacred objects aren’t props—they’re ways devotees connect with the unseen. When myths fall away, Vodou’s core becomes clear: relationship, responsibility, and reverence.

References

- https://steemit.com/culture/@arrrados/haitian-vodou-history-beliefs-and-practices

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haitian_Vodou

- https://haiti.lasaweb.org/en/vodou-history-and-cultural-significance/

- https://www.anthroencyclopedia.com/entry/haitian-vodou

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/explore-timeless-world-vodou-haiti-180963673/

- https://scholar.library.miami.edu/emancipation/religion3.htm