The relationship between Haitian Vodou and Freemasonry is a complex subject that touches on history, sociology, and national identity. In a recent discussion on Radio Télé Canal Bleu, cultural observer Jean Claude Douyon provided a detailed analysis of these two distinct systems. His commentary highlights a deep divide between indigenous spiritual practices and imported European fraternities.

This discussion goes beyond simple comparisons of rituals or symbols. It addresses how Haitians define themselves, how they relate to their ancestors, and how they organize their communities. Douyon argues that the path to national stability lies in embracing indigenous roots rather than foreign structures.

This article explores the fundamental differences between these traditions, the concept of the bitasyon, and the roles of spiritual leaders in Haitian society. It examines the argument that true authority comes from the land and the ancestors, rather than from external degrees or titles.

The Structural Divide Between Indigenous Practice and Freemasonry

A primary argument presented by Douyon is that Freemasonry functions as an imported system that does not naturally align with Haiti’s spiritual ecosystem. Freemasonry, with its origins in European guilds and Enlightenment philosophy, relies on a hierarchical structure of lodges and degrees.

Critics like Douyon argue that this structure remains foreign to the organic, family-based spirituality of the Haitian majority.

In this view, when public figures or leaders emphasize their status as “great masons,” they may be signaling an attachment to external validation rather than local reality. The argument suggests that the symbols and rituals of Freemasonry, while powerful in their own context, do not tap into the ancestral energy that drives Haitian culture.

They are viewed as blueprints from abroad rather than vegetation that grew from the soil.

By contrast, Haitian Vodou is presented not merely as a religion, but as a total system of life derived from African origins and adapted through the struggle for independence. It is described as a “lived experience” rather than a speculative philosophy.

For proponents of this view, the disconnect between Haiti’s leaders and the population stems from a reliance on these imported frameworks instead of the indigenous spiritual constitution.

The Bitasyon: The Spiritual Anchor of the Family

To understand the contrast with Freemasonry, one must understand the concept of the bitasyon. The bitasyon is the ancestral land or family homestead where generations have lived, died, and been buried. It is the physical and spiritual center of the extended family, often referred to as the lakou system.

Douyon emphasizes that Haitian spirituality is rooted in this specific geography. The connection is biological and spiritual; when a child is born, the umbilical cord is often buried on the land, tying the individual to that specific spot forever. This creates an unbreakable bond between the living, the land, and the ancestors who reside there.

Life on the bitasyon is governed by community rules and seasonal rhythms. There are specific times for planting, harvesting, and honoring the spirits of the land. This organic discipline stands in sharp contrast to the chartered, administrative organization of a Masonic lodge. The bitasyon provides identity and protection that is inherited by blood and location, rather than applied for and granted by a committee.

Initiation as Education, Discipline, and Service

The concept of initiation is central to both systems, but the interpretation differs significantly. In the context of Haitian Vodou, initiation (often referred to as Kanzo in the Rada rite) is described as a rigorous form of education. It is not simply about learning secret handshakes or passwords, but about mastering specific skills necessary for community survival and spiritual balance.

Douyon compares initiation to attending a university or a trade school. An initiate might learn the medicinal properties of local plants, the complex rhythms of the drums that call the Lwa (spirits), or the psychological tools needed to mediate family disputes.

The goal is to transform the individual into a servant of the community, capable of handling the “four elements” and maintaining order.

Furthermore, there is a belief that every Haitian born on a bitasyon possesses a form of “natural initiation.” By growing up within the rules of the lakou, participating in annual protective baths, and observing the taboos of the family spirits, they are already integrated into the system.

This challenges the idea that one must join a secret society to gain spiritual standing; the standing is inherent in one’s heritage.

The Role of Spiritual Guardians and the Lwa

In the indigenous worldview, protection and guidance come from the Lwa, the spiritual entities that serve as intermediaries between the Creator (Bondye) and humanity. These are not distant abstractions but are often viewed as older members of the family.

Figures such as Papa Legba, who is believed to control the crossroads and gates, play a vital role in daily movement and travel.

Douyon notes that these spiritual guardians follow a person regardless of where they move. A person may migrate to Port-au-Prince or abroad, but the spirits of their bitasyon remain with them.

This concept is often referred to as walking with “invisible arms.” It implies that a person’s safety relies on their relationship with these guardians rather than on physical weapons or political connections.

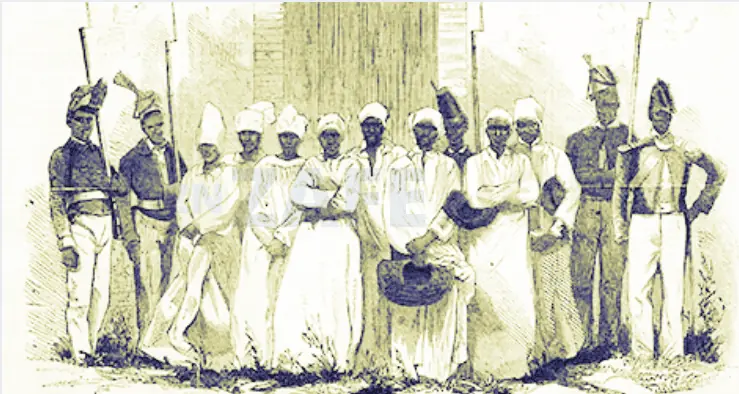

This perspective reframes historical events like the ceremony at Bwa Kayiman. It is presented not just as a political meeting, but as a moment where diverse African groups unified their spiritual strategies. The success of the Haitian Revolution is attributed to this alignment with the Lwa, reinforcing the idea that national strength comes from indigenous, not imported, sources.

Distinguishing the Oungan from the Bokò

A critical distinction in this discussion is the difference between an Oungan (or Manbo for women) and a Bokò. While outsiders often conflate the two, practitioners see them as having different functions and ethical mandates. An Oungan is typically a priest of the Ginen (ancestral) tradition, focused on healing, community stability, and serving the Lwa.

The Oungan acts as a doctor, counselor, and judge within the lakou. Their authority is derived from their ability to maintain harmony between the living and the dead. Douyon emphasizes that this role is one of benevolence and care. The focus is on “treating” the community and ensuring that families remain healthy and united.

Conversely, a Bokò is often described as an independent spiritual worker who may work with “both hands”—meaning they deal with forces that can be used for aggressive or transactional purposes. Douyon warns against the commercialization of spirituality often associated with this path, such as paying for “cards” or magical protections.

He argues that true spiritual authority is earned through service, not purchased.

Governance and the Necessity of Thanksgiving

The conversation extends into the realm of national governance. The argument is made that Haiti has suffered because it has failed to formally acknowledge and thank the spiritual forces that assisted in its liberation. This view suggests that the state has historically marginalized the very practices that made the nation possible.

Douyon proposes that good governance requires collective spiritual acts: specifically, ceremonies of forgiveness and thanksgiving. These would not be mere symbolic gestures but functional rituals intended to reconcile the nation with its history. This aligns with the belief that the country is a collective entity with a spiritual debt that must be paid through respect and remembrance.

From this perspective, political corruption and instability are symptoms of a spiritual imbalance. When leaders adopt foreign models like Freemasonry while ignoring the bitasyon, they sever the roots that provide stability. The call is for a return to a governance style that respects the “rules of the yard” (regleman lakou) on a national scale.

FAQ

What is the main difference between Haitian Vodou and Freemasonry?

Haitian Vodou is an indigenous spiritual system rooted in African ancestry, family land (bitasyon), and community service. It is organic to the history and culture of Haiti. Freemasonry is a fraternal order of European origin that operates through lodges and degrees. Critics argue Freemasonry is an imported structure, while Vodou is the natural spiritual foundation of the Haitian people.

What is a bitasyon in Haitian culture?

A bitasyon is the ancestral family land. It serves as the physical and spiritual headquarters for an extended family. It is where ancestors are buried and where family spirits reside.

Being connected to a bitasyon gives a person their identity, protection, and spiritual obligations. It is the center of the lakou system of communal living.

Are all Haitians considered initiated?

According to the perspective shared by Jean Claude Douyon, Haitians born into the bitasyon system possess a form of natural initiation. By following the rules of their community, participating in seasonal rituals, and respecting family taboos, they are already integrated into the spiritual system.

This contrasts with formal initiation into secret societies, suggesting that daily life in the province is its own form of spiritual discipline.

What is the difference between an Oungan and a Bokò?

An Oungan (priest) or Manbo (priestess) is a community leader ordained to serve the spirits (Lwa) and the community through healing, counseling, and maintaining order. Their work is generally associated with the “Ginen” or cool, ancestral path.

A Bokò is an independent spiritual worker who may operate outside the communal structure and is often associated with more aggressive or transactional magic.

Who is Papa Legba?

Papa Legba is one of the most important Lwa (spirits) in Haitian Vodou. He is the guardian of the crossroads and the opener of gates. No ceremony can begin without invoking him to open the door between the human and spiritual worlds. In the context of migration, he is seen as the force that allows people to travel and move while maintaining a connection to their home.

Why is Bwa Kayiman important to this discussion?

Bwa Kayiman was the site of a ceremony in 1791 that is widely credited with launching the Haitian Revolution. It represents the moment when enslaved Africans unified under indigenous spiritual leadership to fight for freedom. In the debate between Vodou and Freemasonry, Bwa Kayiman is cited as proof that Haiti’s strength comes from its own spiritual roots, not from European institutions.

What are the “invisible arms” mentioned in the article?

The term “invisible arms” refers to the spiritual protection provided by ancestors and Lwa. The belief is that a person who honors their spirits and follows the rules of their bitasyon is protected by forces that cannot be seen. This protection is considered superior to physical weapons because it guards the person’s spirit and destiny wherever they go.