Haiti became the first Black republic in 1804 after enslaved people overthrew France’s brutally profitable colony of Saint-Domingue and linked emancipation to sovereignty.

Jean-Jacques Dessalines’s Declaration of Independence turned a military victory into a public, legal break with the plantation order and asserted self-rule in a world still built on slavery.

Haiti’s example reshaped abolitionist arguments and terrified slaveholding powers, even as diplomatic isolation and France’s coerced “independence debt” drained resources for generations.

This page explains what “first Black republic” meant in practice, what happened in 1804, how Haiti was punished after victory, and why the legacy still matters today.

Key Takeaways

- Haiti’s 1804 independence created the first Black republic, linking emancipation, sovereignty, and a new post-slavery political order.

- The revolution shattered Saint-Domingue’s plantation system, proving enslaved people could defeat an imperial power and govern themselves.

- Haiti forced the Atlantic world to treat emancipation as a political reality, not just a moral argument.

- Major powers punished Haiti through delayed recognition, costly trade barriers, and France’s coercive indemnity, turning “recognition” into long-term extraction.

- Haiti’s legacy still informs debates on racial justice, reparations, and sovereignty, especially when poverty is discussed without its historical causes.

Quick Facts (Dates That Anchor the Story)

- 1791: Enslaved-led uprising begins the Haitian Revolution.

- January 1, 1804: Independence declared in Gonaïves; Saint-Domingue becomes Hayti.

- 1805: Constitution rejects slavery and attempts to close legal pathways back to the colonial racial order, including defining citizens under a single political identity (“Black”).

- 1825: France demands an indemnity as the price of recognition, enforced under threat.

- 1862: The United States authorizes diplomatic relations with Haiti during the Civil War (after decades of delay).

What Was Haiti Before Independence (Saint-Domingue)?

Before it became Haiti, the western part of Hispaniola was France’s colony of Saint-Domingue, a plantation empire built on enslaved African labor and organized for export wealth.

Sugar and coffee enriched merchants and investors across the Atlantic, while plantation mortality stayed high and the forced import of captives continued. Violence was not incidental. It was the system’s daily operating method.

Power was concentrated among white planters and colonial officials. Free people of color could own property and sometimes enslaved labor, yet faced legal discrimination and political exclusion. Enslaved workers, maroon communities, and urban laborers maintained culture, religion, and resistance networks under constant policing.

That mix of extreme profitability and extreme coercion made Saint-Domingue both wealthy and unstable, primed for revolution once imperial crisis and local grievances collided. Saint-Domingue background

What Made Haiti the First Black Republic?

Haiti became the first Black republic because the revolution did not end with partial reform or elite replacement. It ended with enslaved people and their allies defeating a major empire and founding a state designed to keep slavery from returning.

The Haitian Revolution began in 1791 and moved through shifting alliances, civil war, and international war. Emancipation expanded during the conflict, and the revolutionary outcome was not simply “freedom from France.” It was a political project that tied freedom to sovereignty.

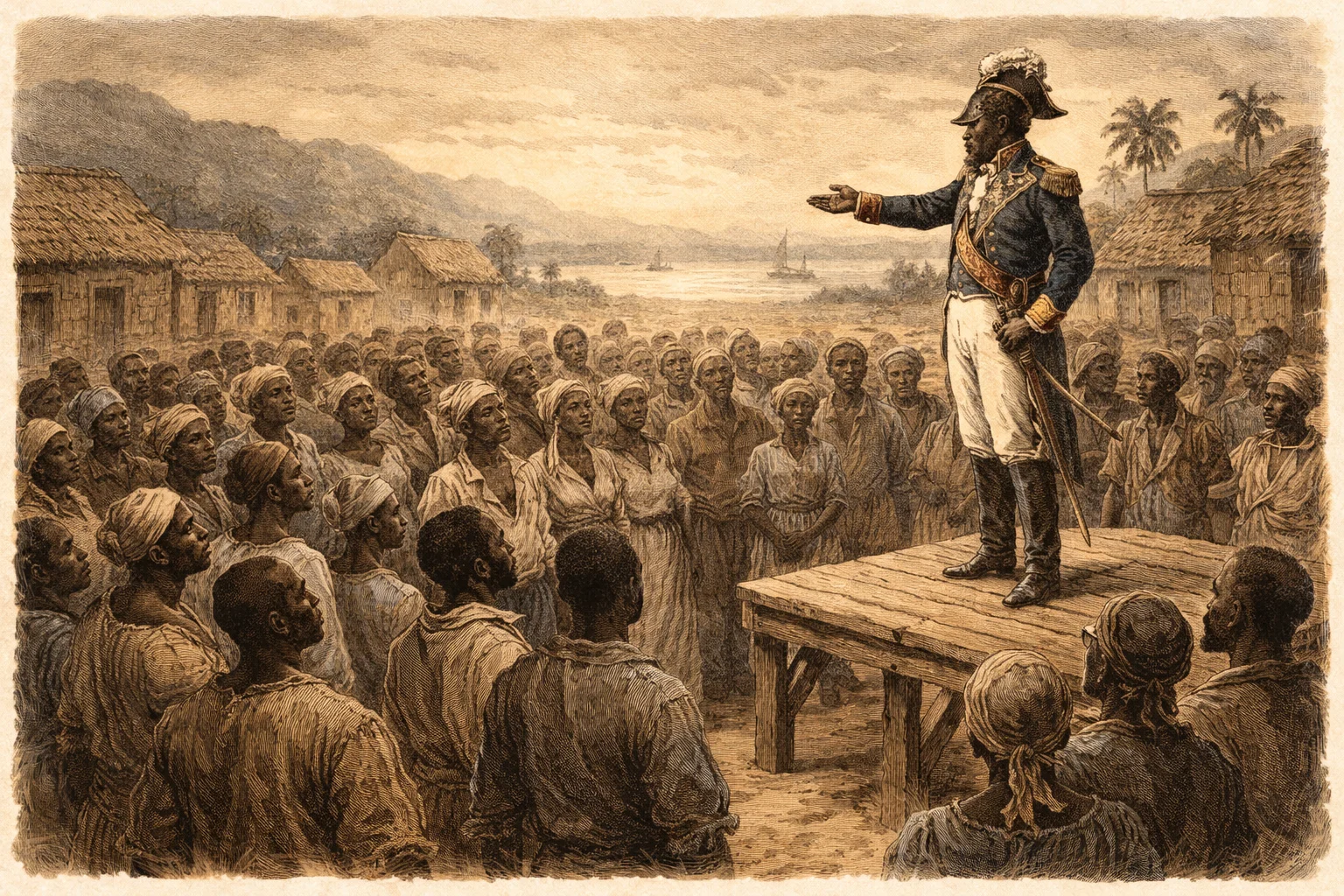

After independence, Haitian leaders reclaimed the name “Hayti” and rejected Saint-Domingue’s plantation order as the foundation of political life. The combination of mass emancipation, military victory, and self-rule made Haiti unprecedented in the age of revolutions. Dessalines and the Declaration

What Happened in 1804, and Why?

Independence on the battlefield only mattered if it became a public, legal break with colonial rule. That is what happened in 1804.

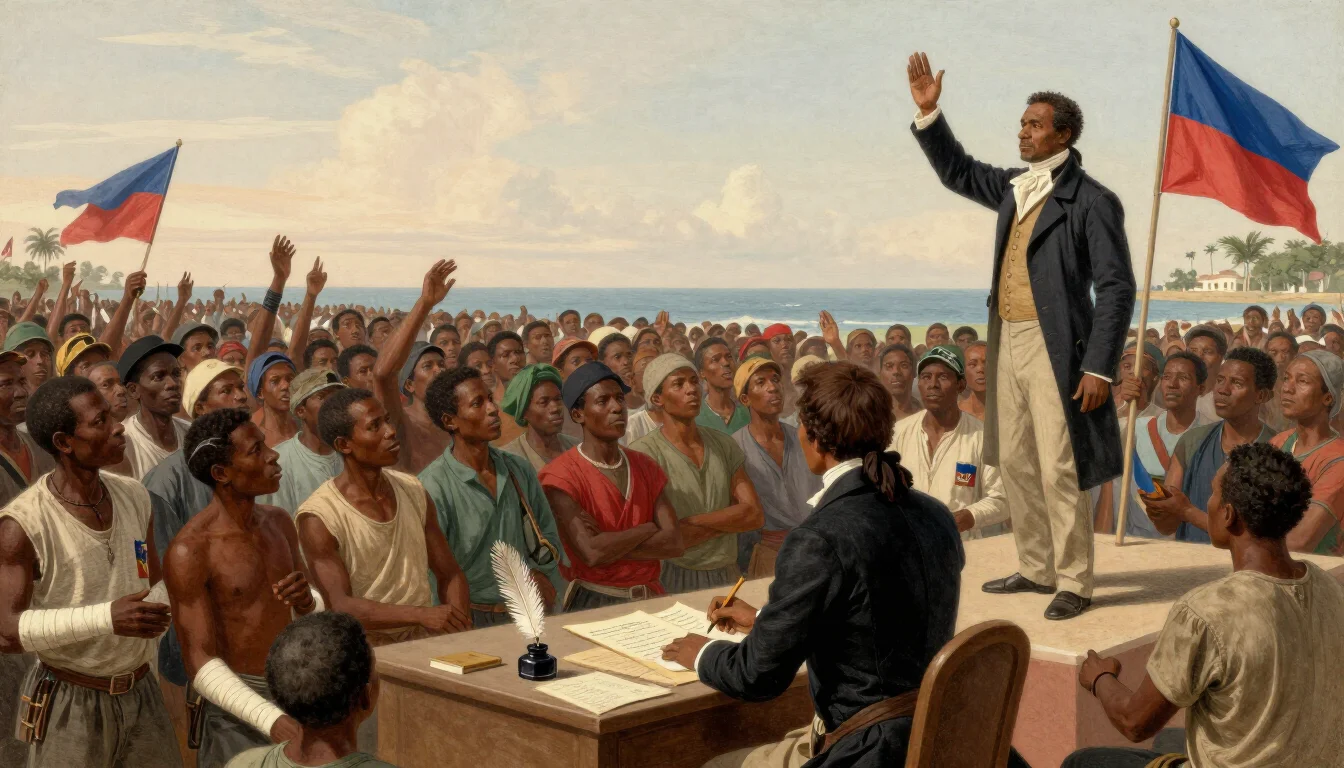

On January 1, 1804, in Gonaïves, Jean-Jacques Dessalines declared independence, ending Saint-Domingue and restoring the name Hayti. The declaration turned revolutionary control into statehood, creating a new Caribbean nation defined by formerly enslaved people rather than colonial elites.

The independence text is commonly associated with Dessalines’s secretary, Louis Boisrond-Tonnerre, and it framed independence as a permanent break backed by a vow to resist any return of slavery or French rule. 1804 declaration source

What Did “First Black Republic” Mean in Law?

“First Black republic” was not only a description of leadership. It became part of how the new state defined citizenship in a hostile Atlantic world.

The 1805 Constitution rejected slavery and attempted to close legal pathways back to the old racial order. One of its most discussed provisions declared that Haitians would be known by the generic name of “Black”, a political claim meant to collapse the colonial color hierarchy that justified bondage.

In context, this was not about biology. It was a sovereignty strategy. Haiti was stating that citizenship would not be graded by proximity to whiteness and that the republic would not accept the plantation caste system in legal form. 1805 Constitution (text)

What Came Next After 1804 (State-Building and Struggle, 1804 to 1825)

Independence did not end conflict. It changed what the conflict was about: how to govern, how to rebuild an economy after plantation collapse, and how to defend sovereignty in a world that wanted Haiti contained.

Dessalines ruled first and sought to stabilize the new state quickly, including through authoritarian measures and attempts to force agricultural production. After his assassination in 1806, Haiti split into rival regimes, including Henri Christophe in the north and Alexandre Pétion in the south.

This period matters because the outside world often treats Haiti as if “1804 happened” and then nothing else counts. In reality, Haiti spent its first decades experimenting with constitutions, military defense, labor policy, and diplomacy under constant pressure.

Why Did Empires Fear Haiti’s Independence?

Haiti proved that enslaved people could defeat European armies, abolish slavery, and found a sovereign Black state on former plantation wealth. That example threatened empires built on coerced labor and racial hierarchy.

Leaders feared revolt would spread across the Caribbean and the American South, undermining colonial authority and sugar profits. Recognition was delayed not because Haiti was invisible, but because Haiti was politically dangerous to slaveholding systems.

The United States postponed full diplomatic recognition for decades, then moved during the Civil War. In 1862, U.S. law authorized the appointment of diplomatic representatives to Haiti, a formal shift that reflected changing politics at home as slavery came under direct assault. U.S. law authorizing relations (1862)

How Did Haiti Reshape Global Slavery?

Haiti rewired what slavery’s defenders thought was possible. A revolution begun by enslaved people ended in independence with laws designed to prevent slavery’s return.

For abolitionists, Haiti became proof that emancipation could be defended and governed, not simply imagined. For enslaved and free Black communities across the Atlantic, Haiti was evidence that self-government was real, even when powerful states tried to isolate it.

Haiti’s survival also forced other governments to reveal their priorities. When recognition was delayed, it exposed how strongly slavery shaped diplomacy, trade, insurance, and migration policy in the nineteenth-century Atlantic world.

How Was Haiti Punished After 1804?

After winning freedom, Haiti faced containment. Recognition was stalled. Trade was made expensive through risk pricing, restricted port access, and political hostility. The new state also faced pressure to restore the old property order, including demands tied to former colonists.

Haiti had to fund defense, rebuild governance, and stabilize food production while the outside world treated its sovereignty as conditional. The most damaging coercion came through France’s demand that Haiti pay for recognition.

What Was Haiti’s “Independence Debt” to France?

In 1825, France offered recognition on coercive terms. Under threat of force, Haiti was required to pay an indemnity meant to compensate former French colonists for losses after independence.

The ordinance set the indemnity at 150 million francs, an enormous sum for a new country that had been economically and diplomatically boxed in. Haiti then had to borrow to pay, converting “recognition” into an interest-bearing obligation.

In 1838, the indemnity was renegotiated, reducing the remaining balance. Even with renegotiation, the debt’s structure forced Haiti into long-term extraction through external finance, crowding out public investment for generations. How the debt worked

Is Haiti’s Freedom Called a “Failure”…Why?

Haiti’s freedom is often unfairly branded a “failure” when critics judge the first Black republic by later poverty and political turmoil while ignoring the forces set against it from the start.

International isolation, racist hostility from slaveholding powers, and the coerced indemnity were not side stories. They were core mechanisms that constrained trade, financing, and institution-building. Destabilization was not “natural.” It was repeatedly produced by external pressure interacting with real internal conflicts over labor, land, and governance.

Yes, early Haiti experienced violence and power struggles, and its leaders made choices that remain debated. But treating poverty as proof that emancipation “did not work” turns punishment into a moral verdict against the punished. Haiti’s post-1804 complexity

How Did Haiti Inspire Black Liberation Worldwide?

Haiti’s independence proved that enslaved people could defeat a major empire and build a sovereign state. That turned “freedom” from an abstract ideal into a lived political reality.

News of the victory moved through ports, plantations, and abolitionist networks. It unsettled slaveholding societies while giving oppressed people a concrete reference point for what liberation could look like when defended by arms, law, and collective memory.

Haiti’s story also reminds the world that liberation is not only a moment. It is a struggle to keep freedom intact when powerful systems attempt to reverse it through debt, isolation, and political control. Haiti’s meaning in Black politics

What Could Justice for Haiti Look Like Today?

Justice begins by treating Haiti’s poverty as a historically produced outcome, not a national flaw. That means confronting the extraction that followed 1804, especially the coerced indemnity that bled public resources and redirected national income toward external creditors.

Justice can include acknowledgment, restitution frameworks, and debt relief tied to Haitian-led priorities, not donor fashion. It also means ending political meddling, supporting accountable institutions, and investing in infrastructure, schools, and health systems without punishing conditions.

Most of all, justice means respecting Haiti’s sovereignty and revolutionary legacy. Partnership is not charity. It is overdue recognition of what Haiti changed in world history.

Read more: the long-term burden of the indemnity and debt

Frequently Asked Questions

When did Haiti become independent?

Haiti declared independence on January 1, 1804, in Gonaïves, ending French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue and restoring the name Hayti.

What does “first Black republic” mean?

It means Haiti was the first modern nation-state founded by formerly enslaved people that abolished slavery and asserted sovereign self-rule, rather than remaining under colonial authority or a slaveholding elite.

What was Haiti’s “independence debt”?

It was the indemnity France demanded in 1825 as the price of recognition, enforced under threat, which Haiti financed through borrowing and repaid over time as an interest-bearing obligation.

Why did the United States delay recognizing Haiti?

Because slavery shaped U.S. politics for decades. Recognizing a Black republic born from a successful enslaved uprising was politically explosive in a slaveholding republic. Formal diplomatic relations were authorized in 1862 during the Civil War.

Why is Haitian independence still relevant today?

Because it reshaped the modern meaning of freedom, citizenship, and anti-slavery politics, while its punishment through isolation and coerced debt shows how global power can retaliate against emancipation and sovereignty.

Conclusion

Haiti’s independence shattered the idea that slavery was permanent and that Black freedom was impossible.

In 1804, the first Black republic forced empires to reckon with a revolution they could not control, then punished Haiti through isolation and a coerced debt designed to drain its future.

Calling Haiti’s freedom a failure ignores that sabotage. Haiti’s example still fuels liberation movements, and justice today requires repair, respect, and real sovereignty.

References

- https://www.britannica.com/place/Haiti/Early-period

- https://repository.duke.edu/dc/haitisrc/00001138

- http://www2.webster.edu/~corbetre/haiti/history/earlyhaiti/1805-const.htm

- https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-12/pdf/STATUTE-12-Pg421.pdf

- https://bpr.studentorg.berkeley.edu/2024/07/04/the-forced-freedom-of-haitis-independence-debt/

- https://www.aaihs.org/the-black-republic-the-meaning-of-haitian-independence-before-the-occupation/

- https://haitianstudies.ku.edu/haiti-brief-history-complex-nation

- https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/haitian-independence/