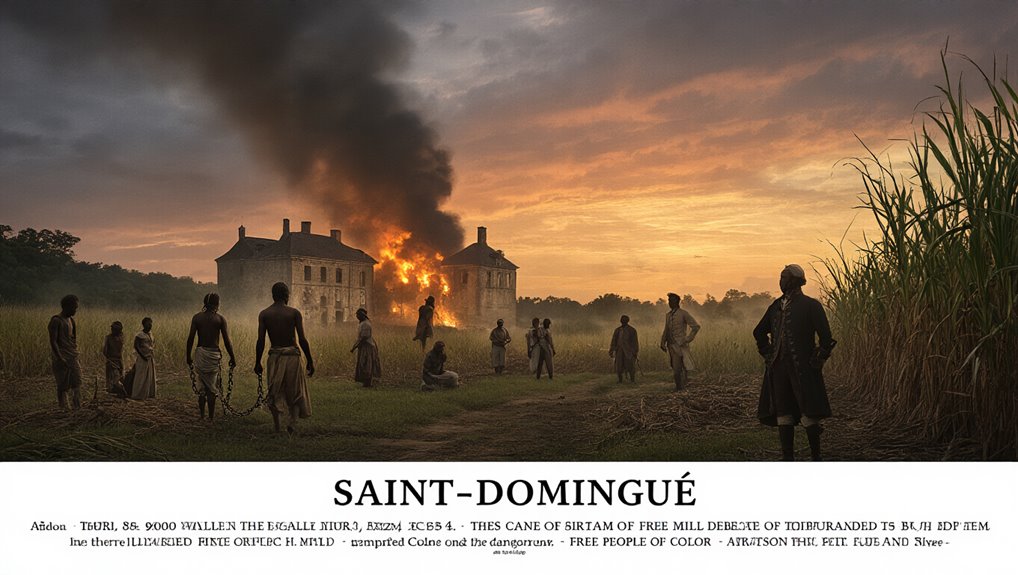

Saint-Domingue (colonial Haiti) was the wealth engine of France’s Atlantic empire, built on sugar and coffee plantations and sustained by slavery. On the eve of the French Revolution, the colony’s population is commonly estimated at about 556,000, including roughly 500,000 enslaved Africans, about 32,000 whites, and about 24,000 affranchis (free people of color).

The wealth was enormous, but political rights and security were distributed by race, status, and faction, not by any universal principle of citizenship.

Direct answer (featured-snippet ready): The Haitian Revolution began in 1791 because three pressures tightened at the same time: an exceptionally violent slave regime that created organized resistance capacity, a racial caste system that denied free people of color equal citizenship, and a political crisis after 1789 that fractured colonial authority.

French mercantilist trade rules (“the exclusif”) and competing white factions intensified instability, but the decisive trigger was a power vacuum that resistance networks could finally exploit.

Key Terms in Plain Language

For readers unfamiliar with the vocabulary: grands blancs were the richest white planters and big merchants; petits blancs were poorer whites (overseers, artisans, sailors, shopkeepers) who often defended status through racial privilege; affranchis were free people of color (freeborn or formerly enslaved), some of whom owned property and even enslaved laborers but were still blocked from equal political rights. Maroon communities were groups of escaped enslaved people who built settlements and survival networks, often in mountainous terrain.

Methodology and Scope

This post is an educational synthesis of widely cited secondary sources and selected primary-source collections. It focuses on causal mechanisms (how pressures translated into mass revolt) rather than offering original archival discoveries.

Where you see quantitative claims (population, trade shares, mortality estimates), treat them as best-known summaries that vary by source and measurement method, and follow the inline links for verification.

Key Takeaways

- Saint-Domingue’s plantation economy generated extraordinary sugar and coffee wealth, but power followed race and faction, not universal rights.

- Enslaved people faced extreme coercion, high mortality, and replaceable labor logic, yet built resistance through sabotage, flight, maroon communities, and trusted night networks.

- Racial hierarchy denied free people of color equal citizenship, making “rights” talk after 1789 both plausible and explosive.

- French mercantilist controls (“exclusif”) shaped prices, credit, and contraband incentives; they aggravated grievances but did not affect every group the same way.

- Timing mattered: authority fractured after 1789, Vincent Ogé’s 1790–1791 rights revolt showed reform could be met with spectacular violence, and by 1791 resistance networks could coordinate mass insurrection.

Quick Timeline: Why 1791, Not “Sometime Earlier”?

- 1789: French Revolution begins. Rights language and political experimentation spread into the colonies through decrees, petitions, assemblies, and print culture.

- Oct 1790 to Feb 1791: Vincent Ogé leads an armed push for political rights for free men of color after colonial authorities refuse implementation. The revolt fails; Ogé is publicly executed, signaling the limits of peaceful reform.

- Aug 1791: Large-scale enslaved uprising begins in the North, scaling rapidly because plantation discipline had already produced networks of secrecy, mobility, and coordinated action.

Key Causes of the Haitian Revolution

Why did Saint-Domingue erupt into revolution? The strongest explanation is not a single “cause,” but an intersection of pressures that created both motive and capacity. Mercantilist controls and plantation credit systems shaped opportunity and resentment.

Racial law structured who could claim citizenship. Most decisively, the slave regime built resistance networks that could scale once colonial authority fractured after 1789. In other words: economic extraction, racialized political exclusion, and organized coercion collided in a moment of institutional breakdown.

Saint-Domingue’s Plantation Wealth and Inequality

Saint-Domingue was regularly described as France’s richest colony because sugar and coffee exports were enormous. Institutional summaries commonly note that the colony supplied a striking share of Europe’s sugar and coffee imports on the eve of revolution.

That wealth, however, hardened inequality because plantation profits linked economic power to political power. Grands blancs dominated key offices and commercial networks. Petits blancs competed for jobs and status, often treating racial privilege as their main protection.

Many affranchis owned property and had education, yet colonial law still treated them as politically unequal. These inequalities mattered because they turned everyday governance (courts, militias, voting, testimony, office-holding) into a permanent conflict over who counted as a citizen.

Slavery’s Violence and Resistance Before 1791

Saint-Domingue’s plantation discipline relied on terror: whipping, mutilation, surveillance, and forced labor paced by harvest demands. Many historians describe extraordinarily high mortality in the colony’s plantation system, with some demographic analyses discussing annual death rates on the order of several percent in peacetime conditions, and higher in crisis years.

This mattered for causation because it created both rage and a sense that the system was designed to consume lives. Yet domination never went unchallenged. Enslaved workers slowed production, sabotaged tools, stole provisions, and fled to maroon communities.

Night gatherings and spiritual practice preserved solidarity, memory, and trusted channels for communication. When authority fractured after 1789, these networks did not need to be invented from scratch. They already existed and could coordinate mass insurrection in 1791. slavery

Racial Hierarchy Shaping Haitian Revolution Tensions

Snippet-ready mechanism: In Saint-Domingue, the racial hierarchy functioned as a system of government: “whiteness” was treated as a qualification for authority in courts, militias, assemblies, and administrative offices.

Daily rules and punishments determined who could vote, testify, bear arms, and participate in governance. When revolutionary language spread from France, these rigid exclusions made equality sound like an existential threat, accelerating polarization and violence.

That hierarchy mapped onto plantation wealth: grands blancs asserted dominance, poorer whites defended status through racial solidarity, and the enslaved majority was reduced to property. Racial categories shaped everyday discipline through pass rules, punishments, and surveillance.

The deeper problem was political: this system left large segments of the population with no legitimate path to representation. Once the language of universal rights entered the colony, conflict over “citizenship” became unavoidable.

For curated collections of documents and visuals that help show how colonial categories were constructed, see the Library of Congress guide. Library of Congress primary resources

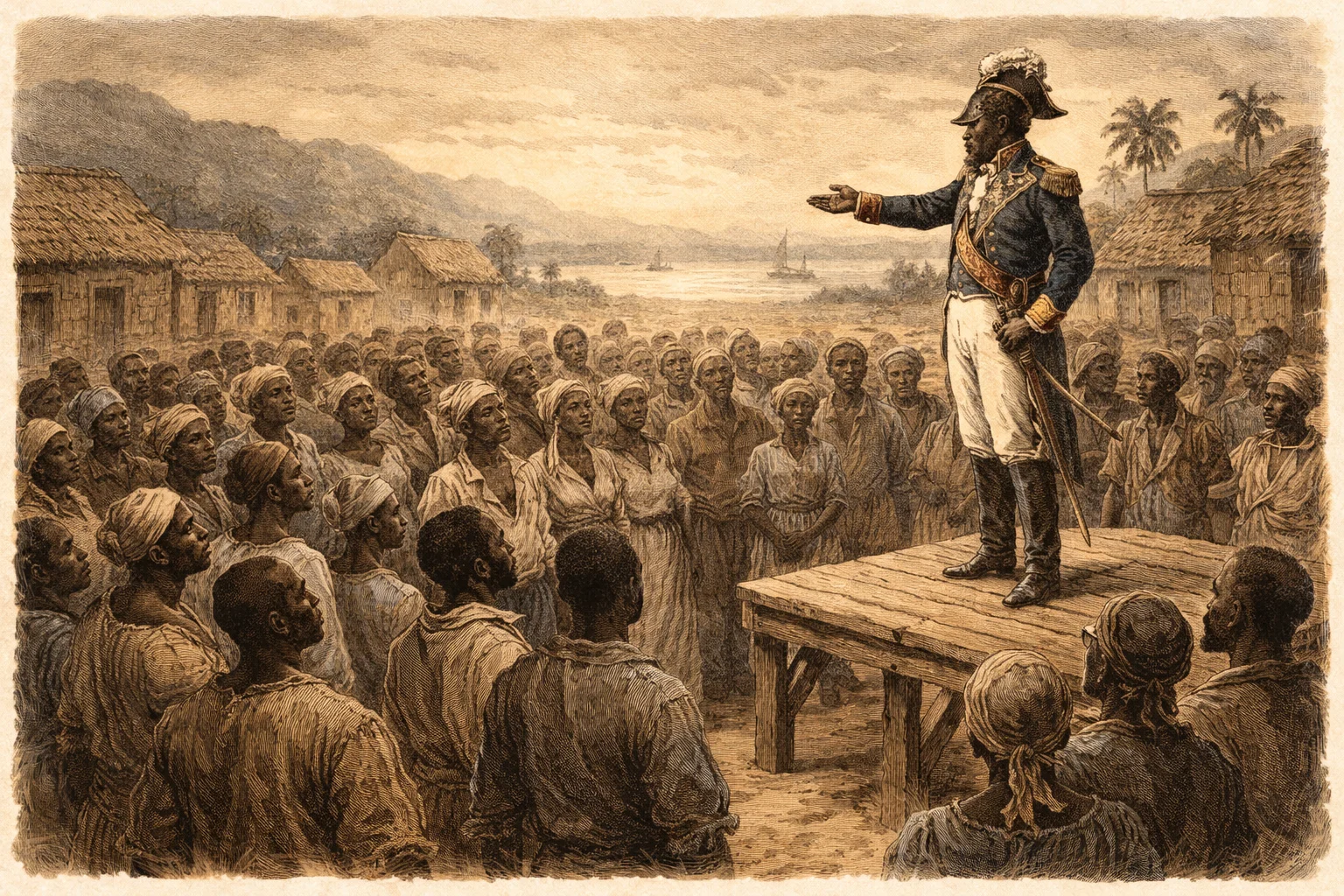

Free People of Color Denied Political Rights

Affranchis paid taxes, owned plantations, and sometimes served in local defense, yet they faced legal and social barriers to voting, holding office, and claiming equal standing in courts and assemblies.

What turned this into a revolutionary flashpoint was timing: the French Revolution created a language of rights and citizenship, and free people of color began pressing claims that framed equality as a legitimate political demand, not a favor.

Vincent Ogé’s revolt (1790–1791) in one clear chain: Ogé returned from France arguing that free men of color should receive political rights consistent with the new revolutionary order. Colonial authorities refused implementation.

Ogé raised an armed force, the revolt was suppressed, and his public execution sent a message that reform could be met with spectacular violence. That did not “cause” the 1791 uprising by itself, but it helped demonstrate that the colonial system would not concede equality peacefully. Political rights

White Planters vs. Poor Whites in Saint-Domingue

Snippet-ready mechanism: White unity was fragile because shared racial identity did not erase class conflict. Grands blancs wanted autonomy and commercial power; petits blancs feared losing jobs and status and often demanded harsher racial restrictions to protect their position.

Grand blancs dominated land, credit, militias, and colonial councils. Petits blancs (artisans, overseers, sailors, shopkeepers) resented elite privilege and used racial status as leverage in local politics.

These white factions sometimes fought each other as aggressively as they fought affranchis demands. The result was not “one white bloc,” but a fractured ruling class that weakened the colony’s ability to respond coherently when multiple crises hit at once.

French Trade Controls That Bred Colonial Resentment

French mercantilism in the Caribbean is often described through the “exclusif,” a trade system designed to route colonial commerce through France. In practice, this shaped prices, credit, and political expectations. Tariffs and routing rules could raise the cost of tools, food, and manufactured goods, while profits were structured through metropolitan merchants and regulations.

However, this did not produce one uniform “anti-France” reaction. Some planters profited within the system, many relied on smuggling and contraband networks to evade it, and competing groups blamed each other for insecurity. The key causal point is that trade rules and enforcement struggles helped destabilize trust in colonial governance and intensified factional politics. mercantilist controls

For a research discussion of how the exclusif could encourage contraband and shape incentives in French Atlantic commerce, see the Yale-hosted paper by Silvia Marzagalli. exclusif and smuggling research

How the French Revolution Reshaped Haitian Revolution Politics

Snippet-ready mechanism: After 1789, the language of rights and citizenship turned local disputes into universal claims. Whites invoked “liberty” to seek autonomy and freer commerce, while free people of color invoked “equality” to demand political inclusion. This split colonial politics and weakened authority at precisely the moment resistance networks were ready to expand.

Revolutionary proclamations, debates over citizenship, and shifting decrees created a moving target for colonial law. Assemblies formed, petitions circulated, and legitimacy became contested rather than assumed.

That contest mattered because colonial rule relied on routine compliance by militias, courts, and administrators. Once those institutions fractured along factional lines, repression became inconsistent and the political opportunity for revolt widened. For a helpful internal explainer on how citizenship debates were framed in the revolution’s broader arc, see: citizenship

Rival Power Blocs That Escalated Revolt Into Revolution

Amid upheaval after 1789, power blocs competed to define who counted as a citizen and who could command the colony. Grand blancs demanded freer trade and local autonomy, while petits blancs defended racial privilege to protect jobs and status.

Affranchis pressed for equal rights and representation. Colonial officials tried to stabilize the system while Paris issued shifting signals, fueling distrust. As elites fought each other, enslaved Africans exploited the chaos. Localized unrest became a colony-wide revolution because the ruling order fractured at the top while resistance capacity was already built at the bottom. primary source

Comparative Context: Why Haiti Was Different

Slave resistance was not unique to Saint-Domingue. The Caribbean saw major uprisings and maroon conflicts across the 18th century, including in Jamaica and elsewhere.

What makes Haiti stand out is that a mass enslaved uprising evolved into a sustained revolutionary war that ended in independence and the permanent abolition of slavery. For a concise overview emphasizing the revolution’s uniqueness as a successful slave rebellion, see: Saint-Domingue Revolution overview

Frequently Asked Questions

What Were the Main Causes of the Haitian Revolution?

The main causes were a brutally coercive plantation slave regime, a racial caste system that denied free people of color equal citizenship, and a political crisis after 1789 that fractured colonial authority. Mercantilist trade rules and white factional conflict amplified instability, but the revolution became possible when resistance networks could finally scale during a breakdown of governance.

When Did the Haitian Revolution Start, and Why Then?

The revolution is typically dated to the large-scale uprising that began in August 1791. “Why then” is explained by timing: rights discourse and political experimentation after 1789 weakened legitimacy, Ogé’s 1790–1791 revolt showed that reform could be crushed violently, and enslaved resistance capacity already existed through maroonage, plantation networks, and trusted communication channels.

Why Did Slavery Lead to Revolution in Saint-Domingue?

Slavery in Saint-Domingue paired extreme violence with an economic model that treated people as replaceable labor. That combination produced both motive (rage, survival, refusal) and capacity (networks of secrecy, movement, coordination). Once colonial authority fractured, those networks could shift from everyday resistance to mass insurrection.

What Did Vincent Ogé Demand, and Why Did It Matter?

Ogé demanded political rights for free men of color consistent with revolutionary claims about citizenship. His revolt mattered because its suppression and public execution dramatized the colonial government’s refusal to concede equality peacefully. It hardened polarization among free people of color and exposed how unstable the colonial order had become.

How Did Foreign Powers Shape the Conflict?

Foreign powers intervened for strategic reasons: European rivals sought to weaken France and seize territory, while French officials shifted policy repeatedly to retain the colony. External pressures mattered, but they became decisive only because internal conflicts had already fractured governance and created openings for revolutionary forces.

Conclusion

The Haitian Revolution grew from Saint-Domingue’s extreme wealth built on brutal slavery and staggering inequality. Enslaved people faced coercion that generated both resistance and organizing capacity. A rigid racial hierarchy denied free people of color equal citizenship, and white factions split over class, status, and autonomy.

Mercantilist trade rules shaped grievances and incentives, including smuggling, but the turning point was political: after 1789, authority fractured, legitimacy broke down, and a revolt that might have been contained became a revolution that remade the Atlantic world.

References

- Study.com. “Haitian Revolution Causes | Overview & History.” https://study.com/academy/lesson/causes-of-the-haitian-revolution.html

- Revista Periferias. “The Haitian Revolution.” https://revistaperiferias.org/en/materia/the-haitian-revolution/

- McKey, C. (2016). “The Economic Consequences of the Haitian Revolution.” Scholars’ Bank, University of Oregon. https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/items/5f9bfaf1-8fe6-473f-9654-0d17fe697ac5

- Rand, David. “Social Triggers of the Haitian Revolution.” University of Miami (Student Project Archive). https://scholar.library.miami.edu/slaves/san_domingo_revolution/individual_essay/david.html

- OER Project. “Economic and Material Causes of Revolt.” https://www.oerproject.com/OER-Materials/OER-Media/HTML-Articles/Origins/Unit7/Economic-and-Material-Causes-of-Revolt

- Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Haitian Revolution | Causes, Summary, & Facts.” https://www.britannica.com/topic/Haitian-Revolution

- Teaching Social Studies. “The Revolt That Changed Everything: The Haitian Revolution’s Immediate Effect on the United States.” https://teachingsocialstudies.org/2023/01/20/the-revolt-that-changed-everything-the-haitian-revolutions-immediate-effect-on-the-united-states/

- International Slavery Museum (Liverpool Museums). “Haiti (Saint-Domingue).” https://slaveryandremembrance.org/articles/article/?id=A0111

- CHNM (George Mason University). “Slavery and the Haitian Revolution” and related documents (including Ogé materials). https://revolution.chnm.org/exhibits/show/liberty–equality–fraternity/slavery-and-the-haitian-revolu

- CHNM Primary Source Context. “Motion Made by Vincent Ogé the Younger…” https://revolution.chnm.org/d/288

- Marzagalli, Silvia (2018). “French Colonial Policy, Warfare, and Eighteenth-Century… (exclusif / smuggling discussion).” Yale-hosted PDF. https://economics.yale.edu/sites/default/files/marzagalli_-_yale_paper_-_30_april_2018.pdf

- Bradshaw, Jim. “Saint-Domingue Revolution.” 64 Parishes. https://64parishes.org/entry/saint-domingue-revolution