In Haitian Vodou, ancestors are not just remembered…they are the dead who have been ritually integrated into a family’s sacred order, with ongoing responsibilities between the living and the departed.

Some lineages elevate certain dead as tovodou (also written tovodu)…family spirits honored through periodic rites and care. Oungan and manbo guide ceremonies for the dead, including rites that reclaim a person’s spiritual essence and lodge it in a govi (a spirit vessel) so the family’s continuity is protected.

At home, many families maintain a clean, dedicated space with water, light, and modest offerings. In the peristil, ancestor services use prayers, songs, and drumming to greet the dead, feed them, and ask for protection and guidance.

Key Takeaways

- In Haitian Vodou, ancestors are deceased kin who become part of a family’s sacred order through lineage and ritual, not simply memory.

- Some ancestors may be elevated as tovodou (family spirits) through periodic rites, creating a structured family cult of care and obligation.

- Post-death rites can include dessounen (also spelled dessounin), a ceremony that “reclaims” the dead person’s spiritual essence and places it in a govi so the family can honor and protect that spirit properly.

- Veneration is a duty of care and remembrance, not worship…neglect is often believed to invite disorder, conflict, or misfortune in the family.

- Ancestor practice happens both at home (simple altar care) and in the peristil (formal services with songs, prayers, and drumming), and it varies by family, region, and lineage tradition.

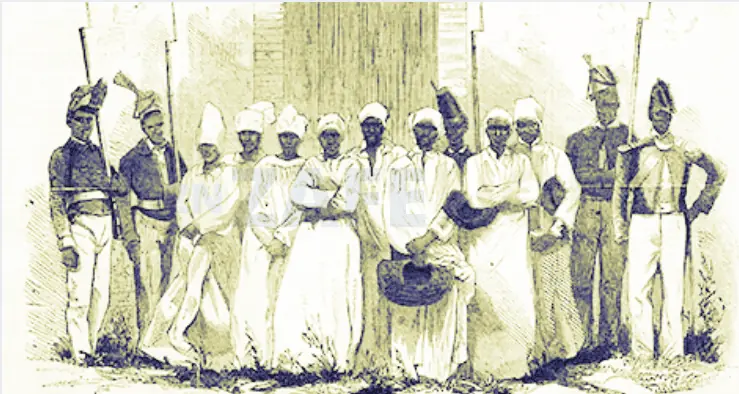

Ancestors in Haitian Vodou: Who They Are

In Haitian Vodou, an ancestor is not defined only by genealogy…it is a spiritual status. People become ancestors through death, family recognition, and ritual processes that place the dead within the moral and spiritual responsibilities of the lineage. In this sense, ancestors remain “family” in an active way: they can bless, warn, protect, and also demand care.

It also helps to separate three related categories:

- Ancestors (family dead): the deceased of a lineage who remain involved in family life through care and obligation.

- Tovodou (elevated family spirits): ancestors honored with a more formalized family cult, sometimes centered on a dedicated ancestral shrine.

- Lwa: powerful spirits of Vodou “nations” (Rada, Petwo, Gede, and others) who serve broader social and cosmic roles beyond one household.

Many families experience these categories as connected: ancestors are kin and “close,” while lwa can be larger forces served through temples, lineages, and community rites. In practice, the living may seek ancestors for intimate family guidance while serving lwa for protection, justice, healing, and spiritual order.

How the Soul Is Understood: Why Govi and Dessounen Matter

Vodou does not treat death as a simple disappearance. Many Haitian Vodou traditions describe the person as having multiple spiritual components…often explained through terms such as gros bon anj and ti bon anj (language and interpretation vary by lineage). The point is practical: after death, the family has responsibilities to stabilize what remains of the person spiritually and to prevent spiritual disorder for the household.

One well-known rite described in multiple accounts is dessounen (also spelled dessounin). It is often explained as a ceremony that “reclaims” a part of the person’s spiritual essence so it can be housed and cared for rather than left vulnerable. A common description links this rite to the idea of retrieving the spirit “from under the water,” sometimes after a significant waiting period, and then placing it into a govi, a covered vessel that becomes a stable spiritual home for that essence.

Death, dying, and the soul in Haitian Vodou

Tovodou and Ancestral Shrines: What “Tovodou” Means

Some families describe a deeper level of ancestral status called tovodou (sometimes written tovodu). In that framework, a lineage may honor certain ancestral spirits as “family gods” through periodic ceremonies, with responsibility shared across the household or extended kin network.

In some accounts, tovodou may be associated with an ancestral shrine, sometimes described as being established through a rite and then maintained through recurring offerings, songs, and formal respect.

This does not mean every family does the same thing. Some families focus on modest home remembrance, while others maintain more formal shrine traditions. The key idea is consistent: ancestral care is structured, recurring, and relational, not a one-time memorial.

Veneration vs. Worship in Haitian Vodou

In many Vodou communities, veneration is best understood as kin duty and ongoing care, not “worship” in the sense of declaring ancestors as supreme gods. The relationship is shaped by love, gratitude, fear of neglect, and obligation. Families often describe ancestral care as practical: maintaining balance in the household, protecting children, supporting health and livelihood, and preserving moral continuity.

Neglect is sometimes believed to invite problems…not as punishment from a distant deity, but as a sign that the household’s relationships and spiritual boundaries have fallen out of order. That is why cleanliness, routine, and respect matter as much as “belief.”

How to Honor Vodou Ancestors at Home: Altar Basics

Many families begin with a simple, clearly dedicated space…an ancestral altar that is kept clean and separate from casual clutter. The details vary by family and temple tradition, but a respectful “baseline” usually includes:

- Fresh water (refreshed regularly)

- A small light (often a candle, used safely)

- A clean cloth (often white, depending on tradition)

- Identifiers (photos, names, inherited items, or simply spoken acknowledgment for “known and unknown” ancestors)

- Modest offerings (for example coffee, fruit, or food…always removed respectfully and kept hygienic)

Most importantly, keep the practice simple and respectful. Advanced rites involving spirit vessels or lineage-specific ceremonies are not “DIY” activities…they are traditionally guided by trained practitioners, and the correct forms vary by lineage. When in doubt, families often treat daily care as relationship-building: clean water, quiet prayer, gratitude, and consistency.

Vodou Ancestor Service in the Peristil: What to Expect

In the peristil (also spelled peristyle), ancestor services are communal and disciplined. A priest or priestess…an oungan or manbo…directs prayers, songs, and ritual order, while drummers establish the cadence and the congregation participates through call-and-response. Many peristil spaces center movement around a central post often called the poto mitan, which is treated as a key spiritual axis within temple space.

Ancestor services can also overlap with broader Vodou calendars, including observances connected to the dead and to the Gede spirits. Names of family dead may be spoken, especially for those recently reclaimed through dessounen traditions. Participants follow the officiants’ instructions on posture, movement, and boundaries because ritual order is part of spiritual safety.

Offerings and Signs: How Ancestors Guide Daily Life

Families often describe offerings as the everyday “line” that keeps ancestors close and attentive. Guidance is not always dramatic. It can arrive as recurring dreams, a persistent sense of warning, an unexpected resolution to a problem, or a feeling of “being pushed” away from harm. When clarity matters, a family may seek divination from a trusted oungan or manbo rather than guessing at signs.

Because ancestors are kin, they are often experienced as nearer than national lwa for household decisions: family conflict, travel choices, child welfare, livelihood risk, and protection. The relationship is best understood as ongoing care…the living honor the dead, and the dead keep watch over the living.

Common Misunderstandings About Vodou Ancestors

- “Anyone can do every ritual at home.” Daily respect is common, but lineage-specific rites (including spirit-vessel traditions) are typically guided by trained practitioners.

- “Ancestors and lwa are identical.” Ancestors are family dead with household obligations, while lwa are powerful spirits with broader roles across communities and ritual “nations.”

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Difference Between Ancestors and Lwa?

In many Vodou traditions, ancestors are deceased kin whose relationship is rooted in lineage, obligation, and household care. Lwa are powerful spirits with wider ritual roles that extend beyond one family, often organized by “nations” (such as Rada, Petwo, and Gede). Families may serve both, but they do not serve them in exactly the same way.

What Is Dessounen, and When Does It Happen?

Dessounen (also spelled dessounin) is commonly described as a rite that “reclaims” a part of the dead person’s spiritual essence so it can be housed and cared for, often connected to the idea of retrieving the spirit “from under the water.” Timing and details vary by lineage and temple tradition, so families typically follow the guidance of experienced practitioners.

What Is a Govi in Haitian Vodou?

A govi is commonly described as a covered vessel used to house a reclaimed spiritual essence of the dead so that it is stable, protected, and properly cared for within family practice. It is not simply an object…it represents a relationship and a responsibility, and its handling is typically guided by lineage-specific rules.

Can Non-Haitians Respectfully Honor Ancestors in This Way?

Respect is possible, but caution is important. Many people can honor their own ancestors with simple remembrance, cleanliness, prayer, and gratitude. Working within Haitian Vodou lineage practices is different and usually requires legitimate guidance, consent, and accountability. It is best to avoid claiming Haitian lineage spirits or copying rites without training.

What If I Have No Photos or Names of Ancestors?

You can still honor ancestors without photos or names. Many families speak to “known and unknown” forebears, keep fresh water and a small light, and offer simple prayers of gratitude. If you later learn names or histories, you can add them gently over time.

Are There Risks in Contacting Ancestors Without Initiation?

Some communities teach that there can be risks if someone tries to interpret signs too confidently or attempts lineage-specific rites without guidance. A safer approach is often to keep home practice simple…clean water, quiet prayer, gratitude…and consult a trusted practitioner for anything advanced.

Conclusion

Ancestor veneration in Haitian Vodou is a living relationship built on care, respect, and continuity. The dead remain present not as distant memories, but as kin integrated into a family’s sacred order.

Whether expressed through simple home devotion or formal peristil services, the goal is stability: protecting the household, preserving lineage, and keeping spiritual obligations in balance. Through consistent attention, modest offerings, prayer, and disciplined ritual, families maintain a bridge between the seen and unseen…and the ancestors, in return, keep watch over the living.

References

- Métraux, Alfred. Voodoo in Haiti. (Foundational ethnography)

- Brown, Karen McCarthy. Mama Lola: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn. (Ethnography, Haitian diaspora context)

- Deren, Maya. Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti. (Classic account; terminology varies by edition and translation)